PhD | Nazis imposed order and tranquillity in secondary schools

Historian Nienke Altena researched the influence of the German occupiers on secondary education in the period 1940-1945. “The Nazis wanted nothing to do with special education. They dreamed of a unified school system under state control.”

Nienke, what an interesting topic. How did you come up with it?

“During my studies, I had already done some research into the German influence on the Amsterdam Lyceum. After that, I became a history teacher in The Hague, but the subject continued to intrigue me. There had been some research done on this subject, but it was outdated. I talked to Professor Peter Romijn to see if my thesis could be broadened to include research on Nazi policy at grammar schools, lyceums and the former HBS and MMSThese are types of schools that disappeared with the Mammoetwet (Mammoth Act) of 1968. They were comparable to VWO and Havo. I received a doctoral scholarship for teachers and was able to get started.”

How did the Germans view our secondary schools?

“The Netherlands has a very pluralistic education system, including for secondary schools. Now, but also back then. In addition to public (secular) schools, there were also many special, often denominational schools. That system could lead to a clash with the German rulers because the Nazis did not want anything to do with that pluralism. They dreamed of a public unified school system under the leadership of the state.”

How did that educational vision play out in Dutch schools?

“To give an example: in February 1941, a pastoral letter from the Roman Catholic Church was read from the pulpit. In that letter, the church reiterated its ban on membership of ‘anti-Catholic movements’, including the NSB. As a result, the salaries of clergy teachers were cut by 40 per cent.”

How was National Socialist ideology reflected in education?

“It was not immediately apparent in the curriculum, and that was not really the German occupiers' primary concern. Their main priority was to maintain order and peace in the schools, to suppress any resistance, but also to ensure that the Dutch school struggle would not be revived. That conflict between denominational and public schools had been settled thirty years earlier by subsidising both public and denominational schools, but the Nazis were much more interested in public education. School leaders were responsible for maintaining peace and order, but a “Gemachtigde Orde en Rust” (Authorised Peace and Order) was also established. Its role was, for example, to investigate complaints about anti-German incidents.”

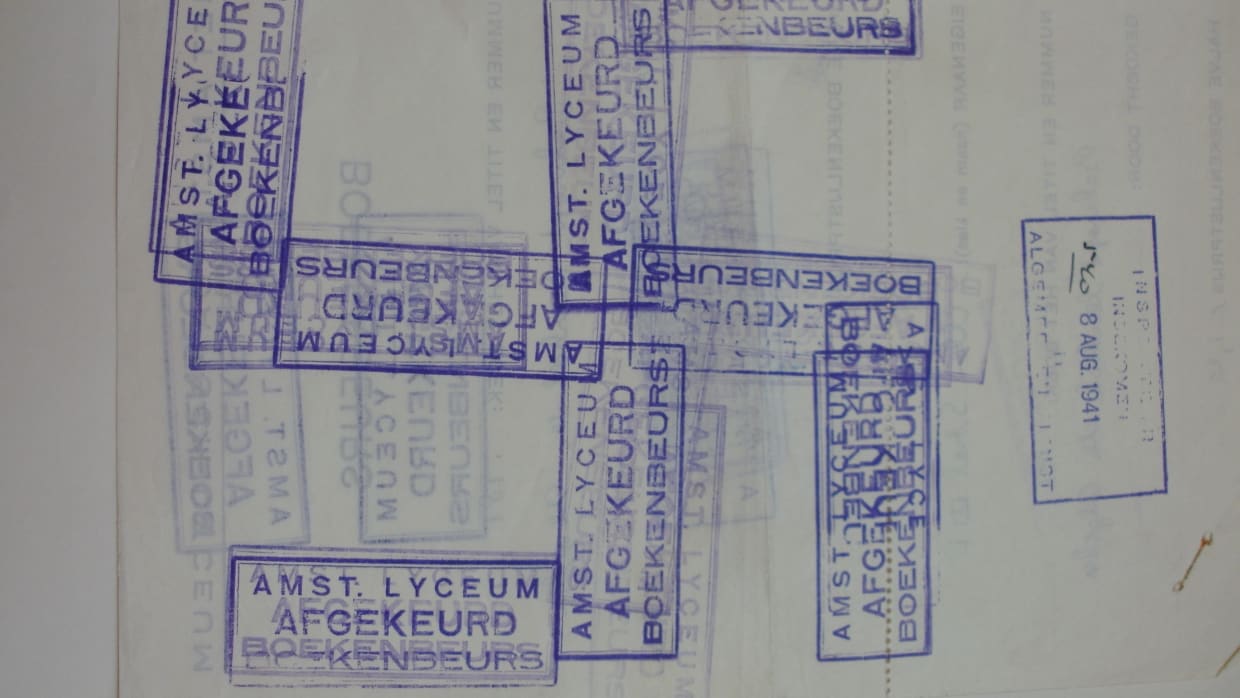

No schoolbook bans?

“There were lists of banned books and teaching materials, mainly history books, of course, in places where Nazi ideology was questioned, where Germany was criticised, or where subjects of a highly national Dutch character were discussed, such as the Royal Family. In such cases, an amendment sheet could be added to the book. The authorities soon realised that controlling the book purge was almost impossible. They made teachers and school leaders responsible for the proper implementation of policy and the maintenance of order and peace. It was unclear what the consequences of not complying with the measures would be. This created an atmosphere of uncertainty in the schools, which was their aim.”

Did the municipal authorities still play a role?

“From the summer of 1941 onwards, more and more NSB mayors were appointed, and they also interfered in public schools. For example, teachers could be forced to collect money for Winterhulp, the National Socialist social welfare organisation, or be forced to take further training at the Opvoedersgilde, the NSB’s educational organisation. Classes could also be forced to visit exhibitions of Nazi art.”

What did the parents think of all this?

“That is difficult to ascertain. However, I have found letters in the archives from parents who complained to the Department of Education about these kinds of National Socialist actions. I have also found complaints from NSB parents who complained about their children being bullied. They were bullied a lot and often. But many parents will also have remained silent for fear of possible reprisals.

From 1943 onwards, teaching became difficult anyway: families were torn apart by employment in Germany, going into hiding, transport became difficult, heating costs skyrocketed and many schools switched to emergency timetables.”

What kind of diploma did you receive if you had attended such a grammar school or HBS during the war?

“I don’t write about this in my thesis. However, something can be said about the pupils in the highest classes who received an emergency diploma before they were sent to the Labour Service (Arbeidsinzet). In 1945, all final-year pupils received their diplomas without having taken an official final exam.

Except for those pupils who were not eligible ‘on the basis of their conduct during the occupation’, i.e. pupils who had voluntarily enlisted to fight in the German army. The 1945/1946 examination took place in a modified form. There was no central written examination, which allowed teachers to take the individual circumstances of the pupils into account.”

PhD thesis by Nienke Altena, In ‘waardigen nationalen geest’ (In a dignified national spirit). Dutch secondary education during the German occupation 1940-1945. Supervisor: Prof. P. Romijn. Date and time: 24 November, 4 p.m. Location: Agnietenkapel. Admission: free.