Outgoing Dutch language and literature professor Fred Weerman: “We need to incorporate the arts into other programs as well”

Language studies have been struggling for several decades. How did this happen and what can we do about it? Fred Weerman, outgoing professor of Dutch language and former dean of the Faculty of Humanities, wrote a book about this phenomenon entitled Het verdriet van de talen (The Sorrow of Languages). “German is still a relatively rich language, and Icelandic is even richer due to the country’s isolated location.”

Why did you want to write this book?

“As a linguist, or as an administrator in the humanities, whenever you talk about your field, you are mostly confronted with three sad reactions: Dutch is impoverishing, languages are disappearing, and language degree programmes are collapsing. A downplaying response to that usually does not help the conversation. And often, a more extensive response does not fit within the scope of a chat either.”

“That’s why I wrote this book. I especially did not want to write only for my fellow linguists. I wanted to create something I could hand over at a party with the message: here is an answer to the questions you had.”

Are languages a source of sorrow?

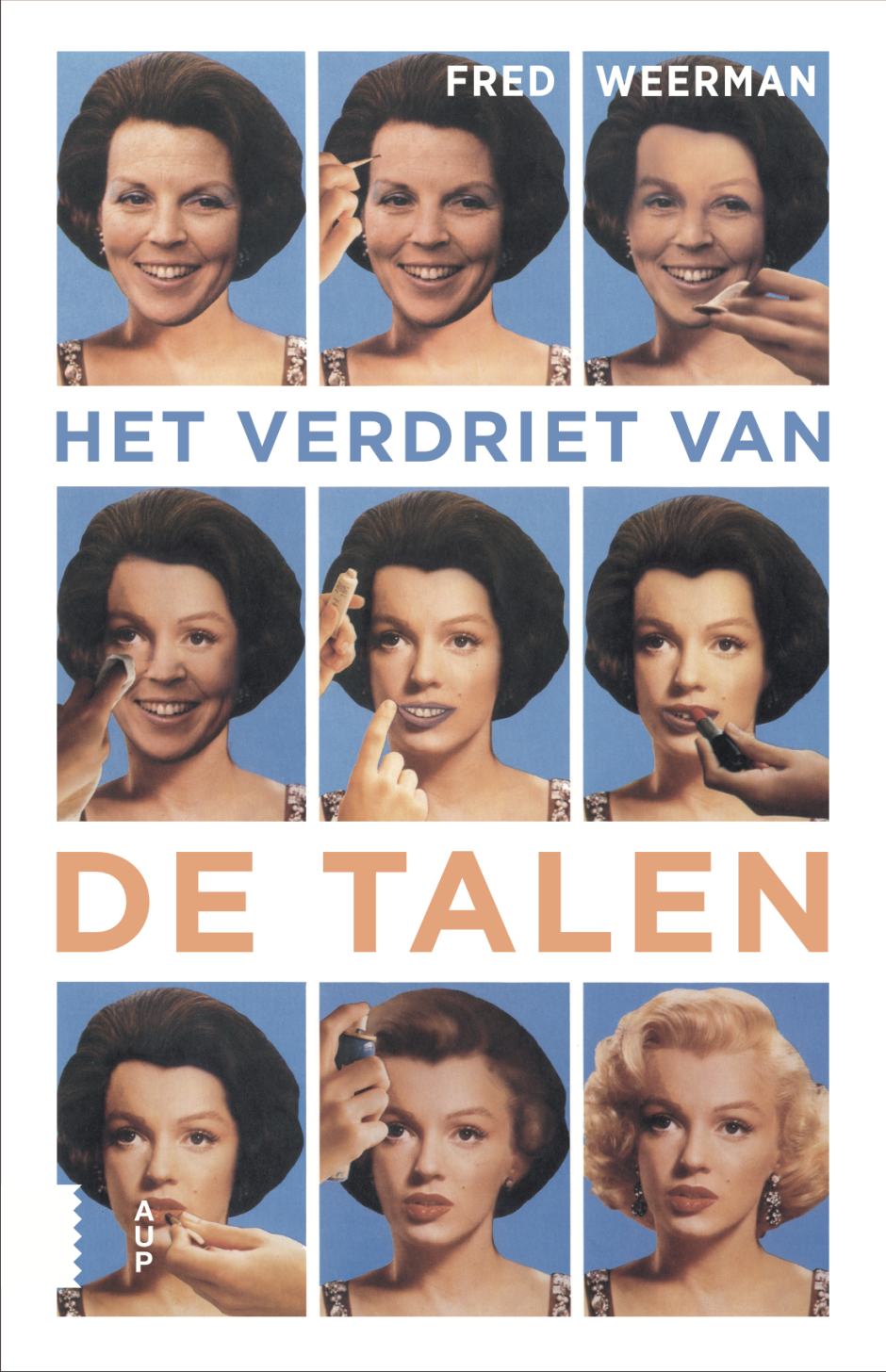

“My research focuses on language change and, at a deeper level, I try to connect that to how people deal with change. Change always brings discomfort. That’s also why I chose the cover image: the metamorphosis of Queen Beatrix into Marilyn Monroe. At first sight, it seems impossible and also feels uncomfortable. Yet, step by step, it does happen.”

You write that Dutch is impoverishing. What do you mean by that?

“Linguists distinguish between richer and poorer languages. The more formal distinctions words have – such as case endings, word classes, and other suffixes – the richer the language. The Germanic languages used to have more such distinctions than they do now, so in that sense they have become poorer. Various explanations have been given for this. My claim is that contact between speakers of different languages explains it best. Centuries of migration and factors such as regionalisation and globalisation play an important role. They can cause languages to lose distinctions in form and even to disappear, as speakers gradually abandon their original language or dialect.”

“This history of migration is not the same for every language. German is still relatively rich, Icelandic – due to the country’s isolated position – even richer. English, by contrast, has lost many distinctions. For example, German still distinguishes between words that combine with der, die and das. English only has the. Dutch lies somewhere in between: we still have common gender (de-words) and neuter (het-words), but the system is under pressure, and the neuter form is being eroded.”

Is it a bad thing if a language becomes impoverished?

“No, not in itself, because in English too you can express yourself wonderfully. But ideally, you would move from a rich to a poor language in one go. The small steps in Dutch make each individual rule simpler for learners, but ironically, they make the overall system less transparent and harder to learn.”

Why don’t we strip Dutch of these distinctions all at once then?

“Because that change would be too big. So we take small steps. That’s the tragedy: we cannot handle the big step. People talk about ‘the decline of Dutch’ when they are irritated by so-called incorrect usage, such as ik besef me instead of ik besef. Or by borrowings from English, such as een beslissing maken (from to make a decision), instead of een beslissing nemen (to take a decision, which is correct in Dutch). The real sorrow lies in the fact that we can only take small steps. That’s the crux of the book. Only under special circumstances are big steps possible.”

How have you seen language degree programmes change over the past fifty years?

“They have become much smaller. And that’s not uniquely Dutch – it’s an international trend.”

“As to why, that’s harder to explain. In general, I saw the appreciation for the humanities decline. Also, financial support from the government decreased. And in secondary school, policy has steered more towards the sciences. The profile culture & society collapsed like a soufflé.”

1989 PhD, Utrecht University

1989 Associate Professor in Dutch linguistics, Utrecht University

1998 – 2001 Associate Professor in Dutch linguistics, University College Utrecht

2001 Professor of Dutch linguistics, UvA

2016 – 2022 Dean of the Faculty of Humanities, UvA

2023 – 2025 Interim Director of the UvA/HvA

“When I went to secondary school in the seventies, that difference did not yet exist. Humanities and sciences were considered equal. I chose Dutch because I wanted to keep my options open. That picture has now completely reversed. Languages are now unjustly depicted as a collection of small, fairly useless degree programmes from which, once graduated, you can hardly earn a living.”

“Student numbers in languages have dropped dramatically, though the problem extends more broadly to the humanities. For a long time, I did not see the decline clearly because of the enormous growth in overall pre-university secondary education pupil and later international students. But the relative share of students choosing humanities has fallen. Over the past thirty years, it has dropped from 16 to 8 percent.”

Why is that a problem?

“There are all sorts of societal issues concerning language and culture, and there are not enough specialists. With current geopolitical developments, expertise in language and culture is more needed than ever. The teaching profession is also facing huge shortages.”

“That’s from a utilitarian point of view. The demand for usefulness has become more prominent in science. We must demonstrate our societal value and make the world a better place, while science is also about understanding the world. That understanding may lead to the conclusion that becoming better is not always possible. The path from understanding to application is often unpredictable.”

“From a scholarly perspective, I also find it regrettable that languages are shrinking. And also for students: the skills you learn in the humanities are skills I wish many more people had.”

What skills are those?

“Anywhere verbal behaviour is involved. Also, the careful analysis of texts and the precise study of argumentation.”

What can we do about it?

“We need to work even more interdisciplinary and embed the humanities into other degree programmes as well. Not so much to survive, but because humanities also benefit other students and because society cannot do without them.”

Fred Weerman, Het verdriet van de talen. Metamorfoses van taal en talenstudies. (Amsterdam, 2025), € 20,- In Dutch only.