Amsterdam is a city steeped in history

The city centre of Amsterdam is steeped in history. With Stourtje, her pocket-sized city walks, historian and UvA alumna Roos Hamelink wants to bring stories of the city centre to the attention of a young audience. Five highlights.

1. Oudemanhuispoort – palace for the poor

From the entrance to the Oudemanhuispoort, on the Oudezijds Achterburgwal, three figures look down on the pedestrians in the street. From left to right, they represent poverty, kindness and old age. In 1602, this was the Oude Mannen en Vrouwen Gasthuis (Old Men and Women’s Hospice), popularly known as the “palace for the poor”, says historian Roos Hamelink. “Strict rules applied: if you complained about the food, you were banished for six weeks. The menu consisted of bread with butter or cheese, meat with vegetables and rice for lunch, sometimes fish or rabbit, and rice porridge or barley in the evening. Fruit was only available in the form of cooked apples and pears. In other words, soft food for people without teeth.”

2. Agnietenkapel - birth of a university

In January 1632, two scholars, Gerardus Vossius and Casparus Barlaeus, opened the Athenaeum Illustre, the predecessor of the UvA, in the Agnietenkapel. The lecture halls were mainly filled with merchants and their sons who, before the markets opened, immersed themselves in philosophy for two hours. It was not until 1877 that the Athenaeum became a municipal university: the University of Amsterdam (UvA). Because the UvA was financed by the city of Amsterdam and the city council appointed the professors, the university has always had a distinctly Amsterdam character: left-wing, liberal and progressive. Even before the war, socialists, communists and married women taught at the UvA, and it was the only university in the Netherlands where you could study economics in the 1920s.

3. Nes – Amsterdam’s first theatre

The Nes was once the centre of Amsterdam’s nightlife. In the attic of a meat hall, a plaque on the corner of the Pieterspoortsteeg still refers to that time, when the so-called ‘Rederijkerskamers’, literary poetry clubs that organised theatre evenings, were located there. Gerbrand Bredero – one of the Dutch playwrights alongside Vondel and P.C. Hooft – lived around the corner and tested his texts on the audience here. “That theatre was different from what we know today,” says Hamelink. “The audience often participated in the play, and people ate, drank and smoked in the auditorium.” Later, the first theatre in Amsterdam emerged from the chambers of the Rederijkers.

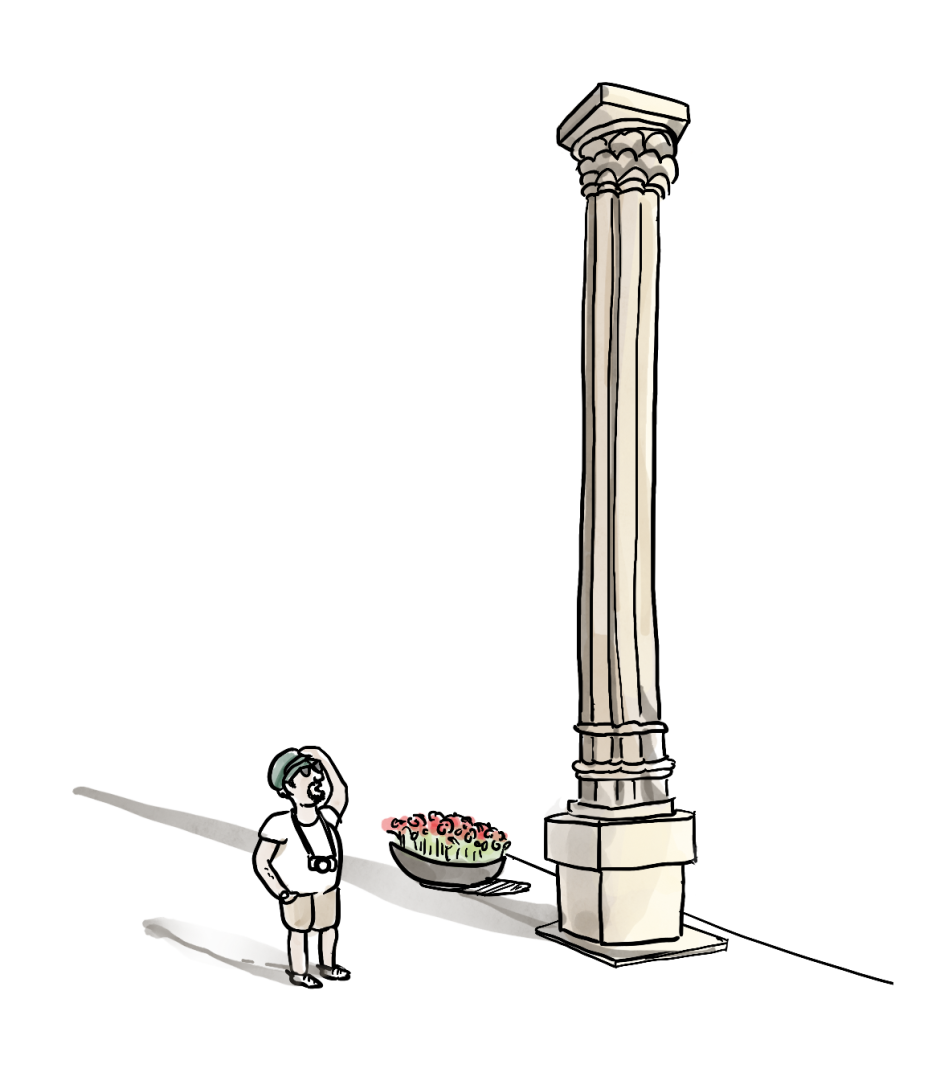

4. Mirakelkolom – a miracle in the Kalverstraat

On 15 March 1345, a man lay dying in the Kalverstraat. He was given a communion bread with his last communion, which he threw up but which then mysteriously refused to disappear. Reason enough to declare the place holy and build a chapel there. The Miracle Column on the Rokin commemorates the last Gothic chapel, which was demolished in 1908. The site became a place of pilgrimage, and on the Saturday after 15 March, the Silent Procession is still held to commemorate the “host miracle”. Hamelink discovered that in the 1960s and 1970s, the procession had another purpose: men from the surrounding villages would sneak away during the procession on the Rokin to visit the prostitutes in the Red Light District.

5. Begijnhof – Cornelia’s Alley

Hidden behind the hustle and bustle of the Spui lies the Begijnhof. Like nuns, the Beguines took a vow of chastity but were allowed to leave the Begijnhof if they wanted to marry. One who did not leave the Begijnhof was Cornelia Arens. She was born in 1621 to wealthy Catholic parents and grew up at a time when the Protestants were taking over the city. The Beguines retained their right to be buried in the now Protestant church in the courtyard, but Cornelia would not have it for all the gold in the world. “I would rather be buried in the gutter than in that desecrated church,” she is said to have said. Nevertheless, she was buried in the church, after which she appeared in the gutter three times, according to legend, and her body was therefore moved.

The origins of Amsterdam

Throughout the city, on weather vanes, churches and facade stones, the cog ship is depicted, sometimes with two figures inside and a small dog. “Even more enjoyable than the toll privilege, the reason why we are celebrating 750 years of Amsterdam this year, is this fairy tale about the origins of Amsterdam,” says Hamelink. The story goes that in the 9th century, Bishop Coenraad of Utrecht took control of Friesland. But his encounter with the stubborn Frisians was anything but smooth: after a storm, he washed ashore more dead than alive and was sent back out to sea on a boat. The young Frisian fisherman Wolfger and his little dog managed to rescue him and sailed back to Utrecht with the bishop. But due to the fog, they arrived at a piece of marshland above Utrecht. The bishop gives Wolfger the land on loan as a token of gratitude and predicts a glorious future for him. The rest is history.

Roos Hamelink (30) studied history and Dutch language and literature in Utrecht and completed a master's degree in public history at the University of Amsterdam. She once travelled to Rome with her boyfriend and devoured many walking guides. With her company Stourtje, a contraction of stads-tourtje (city tour), she writes historical city walks for those who are new to the city or want to (re)discover their own city. After Rotterdam, The Hague and Utrecht, A'dams Tourtje will be published in September.