How sustainable are container homes in a warming climate?

Climate change is causing heat waves with tropical nights to become increasingly common. During these days, container homes heat up like greenhouses and have difficulty releasing the heat. Yet there is still no policy in place to protect residents from the heat. “In this weather, it’s like a sauna.”

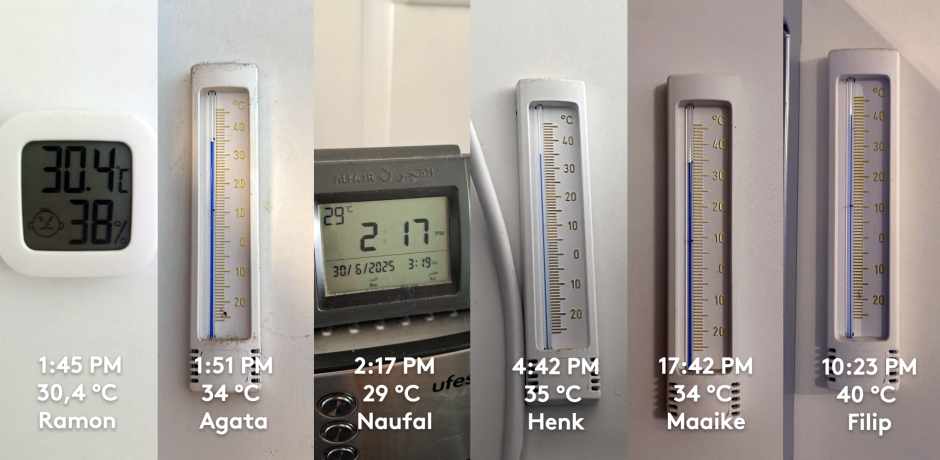

On 1 July at 10.23 PM, the temperature in student Filip’s room on the Spinoza campus reached 40 degrees Celsius. Earlier that day, several students from the student complex in the Bijlmer sent a photo of their thermometer to Folia, which – with the curtains closed and fans on – showed 35 degrees.

The Spinoza Campus consists of 1,250 container homes for students on the outskirts of the Bijlmer, where there have been complaints about the heat ever since it was built in 2012. Container homes were once presented as the solution to the housing shortage in the city. Now, with the climate warming up, the question arises whether it is still sensible to house students there.

“When it’s 25 degrees outside, it heats up to 30 degrees inside,” says UvA student Liza van der Veen, housing officer at the Asva student union and resident of the Spinoza Campus, fortunately on the shady side. The union recently started a petition to raise the issue of heat stress with student housing provider Duwo. “In this hot weather, it’s like sitting in a sauna. It’s difficult to air the rooms because there’s no ventilation and the front door opens onto a gallery.”

On 1 July 2025, the first tropical night of the year was recorded, a night in which the temperature remained above 20 degrees. For many people, this means a sticky and sleepless night. Young adults in particular have difficulty sleeping in the heat.

“Poor sleep leads to health problems and an inability to work or study during the day,” says Anna Solcerova, HvA researcher on climate-proof cities, during a heat symposium at the Amsterdam Public Library (OBA). However, little is known about where exactly night-time heat occurs and how often. Because tropical nights will become more common due to climate change, the Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences (HvA) has launched the 1001 hot nights project, which will use citizen research to measure where night-time heat occurs and how often.

Notorious for being hot

Container homes are notorious for being hot, acknowledges Jeroen Kluck, lecturer in climate-proof cities at the Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences (HvA). “They do have one advantage: the windows are quite small. The more glass a room has, the greater the risk of it becoming hot. And if you can air a container home properly at night and keep the sun out, then it can be fine.”

That is not the case at the Spinoza Campus. The container homes have no external sun blinds and, apart from an extractor fan in the bathroom, no ventilation system. What’s more, the front doors open onto a gallery between the homes without ventilation, which means that residents cannot air their homes properly. As a result, it quickly becomes too hot, with all the consequences that entails. Kluck: “If the homes are too hot, students cannot study properly, and if it doesn’t cool down, you sleep poorly. That causes problems, especially during exam weeks.”

With the petition, the student union Asva wants to get Duwo to take action and install sun blinds on the outside of the building or a ventilation system on the inside.

Measuring heat stress

Duwoners, Duwo’s tenants’ association, has also raised the heat problem with Duwo on several occasions. In those talks, also the heat at other locations such as Science Park and the converted office buildings on Lelylaan were discussed.

Dimitry Grootenboer, board member of Duwoners: “Especially at the end of the day, it is often impossible to dissipate the heat, which is essential for a good night’s sleep. This problem is exacerbated by the hotel-like layout of many buildings: long corridors with rooms on both sides. Because these corridors are escape routes, they cannot be ventilated. During a fire, a ventilation system spreads smoke and fire throughout the building. As a result, heat accumulates and remains trapped.”

Because the students themselves cannot carry out the official temperature measurements required to file a complaint with Duwo, the Duwoners have had external research carried out into the heat in the past. So far without success: Duwo did not follow up on this because, according to them, there was no policy in place.

There are indeed no guidelines for existing homes when it comes to heat stress, says Kluck: “If there were, many homes would already be non-compliant. Moreover, according to current standards, most homes in the Netherlands are already too hot.”

- Make sure the sun doesn’t come in. Try to hang something outside to block the sun, even if it’s just a temporary solution.

- Close your curtains and choose a colour that reflects sunlight: preferably a metallic colour that really reflects light.

- Ventilate the room at night where possible.

- Keep yourself cool. Sleep in thin pyjamas, which absorb sweat, and sleep with a cold hot water bottle.

- Leave the house and find a cool place.

Nevertheless, there are examples of tenants who have succeeded in taking legal action to oblige the housing association to make adjustments to their homes. If this did not happen, the rent was reduced by 20 percent. Kluck: “These were individual cases, but they have made housing associations nervous.”

When asked, the spokesperson for student housing provider Duwo stated that they “always strive for structural solutions to the heat problem” but cannot comment on the situation at the Spinoza Campus within the given timeframe.

In future discussions with Duwo, Duwoners will push for a structural solution to the heat problem, writes Grootenboer, referring to an article in the NOS which states that new-build homes are still designed for the climate of fifteen years ago. “New homes should be designed in such a way that extreme heat can be prevented.”