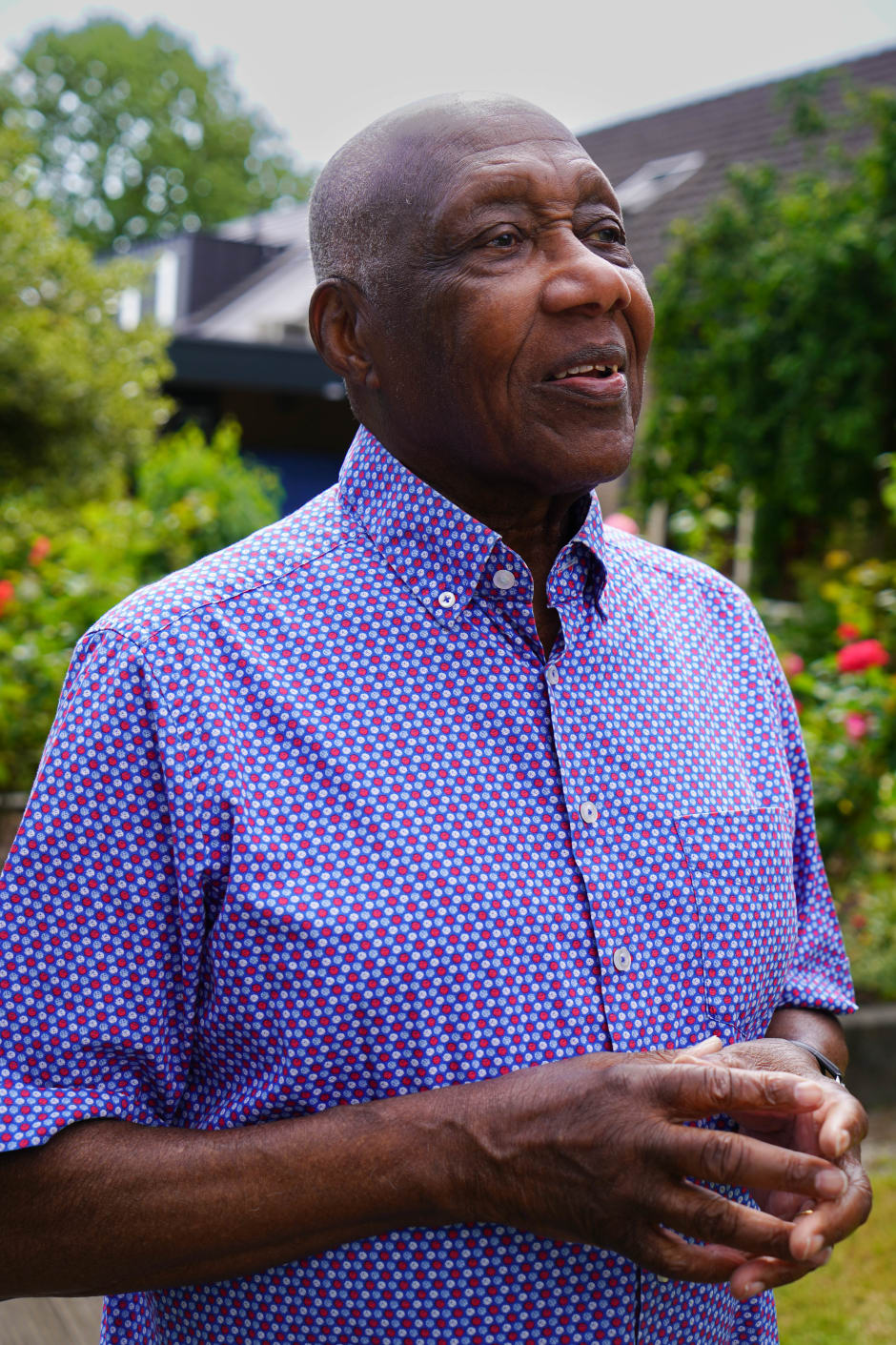

Humphrey Lamur was one of the first Dutch people to research the history of slavery

Next Tuesday is Keti Koti, a Surinamese day of annual celebration. In recent years, there has been increasing attention in Amsterdam for this day commemorating the abolition of slavery. Emeritus professor at the UvA Humprey Lamur is among the first generation of experts in this field. “My great-grandmother was a slave labourer.”

A scientific pioneer: that’s how you could describe 91-year-old emeritus professor Humprey Lamur. In the 1970s, the Surinamese-born sociologist and cultural anthropologist emerged as one of the first academics in the Netherlands to conduct research into the history of slavery. And this despite the fact that, during his childhood in Paramaribo, the subject was hardly ever discussed. The modest Lamur talks about that period in his studyroom at his home in Amstelveen, where he has lived with his wife Norine for forty years.

During your childhood, slavery was never discussed, and you did not even know the word “slave”. Why was that?

“I suppose my parents did not want us to become involved in the history of slavery, to prevent us from being psychologically affected by those criminal stories later in life.

My great-grandmother was a slave labourer as a girl, but even that fact was hardly ever mentioned in the family. Only when we were playing outside would she sometimes say: “You shouldn’t be playing, you should be working, just like I did.” I didn’t know what to make of that, because slavery didn’t play any role in our family. I think my parents wanted to keep us out of it.”

How did you end up learning about that history?

“It was in the Netherlands that I started to hear more about the history of slavery. During my studies, I went to the library to find out more about my great-grandmother’s life. I came across an archive where she was indeed listed as a slave labourer. That’s when the whole history of slavery really came to life for me. It sparked my interest to find out more.”

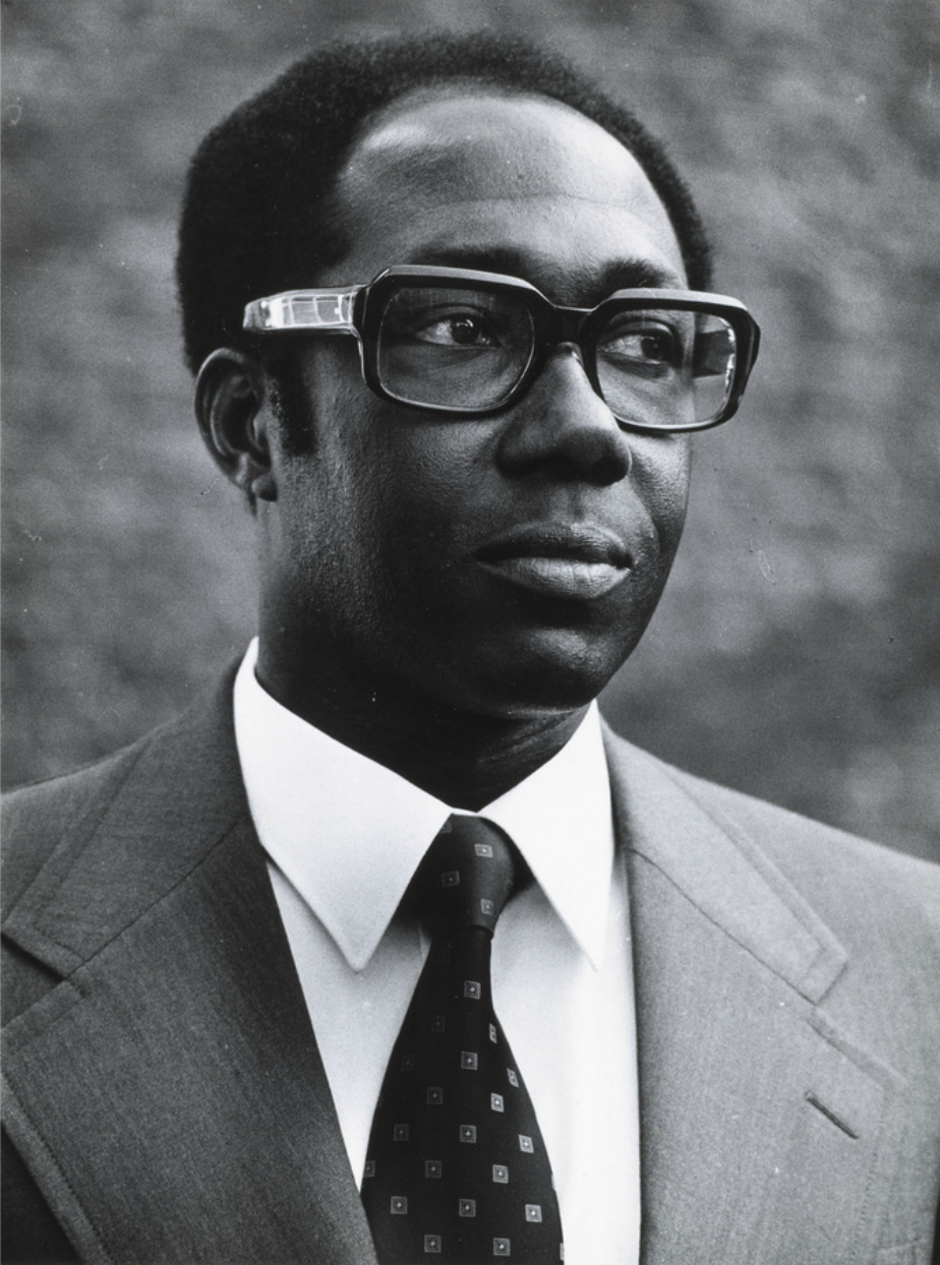

After the Second World War, Lamur moved to the Netherlands, where he ended up as the only black boy at the HLZ school, in the middle of the posh Amsterdam-Zuid neighbourhood. In 1973, he obtained his PhD from the UvA with a thesis on the demography of Suriname. He eventually became a professor of cultural anthropology at the university from 1984 to 1998, but that academic recognition did not come immediately.

“I had written articles about the Surinamese plantation Vossenburg, but colleagues to whom I mentioned this responded with the words: not relevant. I was extremely disappointed, but when I showed the article to an American scientist a little later, he said he wanted to publish it in the United States. A British publisher was also interested in my work. That was a striking contrast, compared to the Netherlands. I don’t think we were that far along at the time. Issues such as slavery and colonialism were seen as things of the distant past that we should no longer concern ourselves with.”

Do you think those Dutch researchers felt uncomfortable with the subject?

“I think it was mainly unfamiliarity. We all think that slavery is so long ago, but here sits Mr Lamur, who spoke to his great-grandmother, who lived through it all. Slavery lasted two hundred years, but many scientists simply weren’t really interested in it.”

Did the UvA fail in this regard at the time?

“I wouldn’t say that, but I was surprised that there was so little interest.”

What has changed in the Netherlands over the past fifty years with regard to the history of slavery?

“I think the slavery issue really came to the fore when more and more Surinamese people came to the Netherlands. That’s how the subject gained public and political attention. But the focus is still mainly on what happened back then. The wealth accumulated by the Netherlands, slaves who were treated like animals, burned alive or raped. Those are the stories we know today, and the issues that arise when we talk about that past. But what receives less attention is the impact of slavery on today’s descendants. That impact is still very significant.”

Lamur pulls out a printed copy of a One World article from 2022, in which police commissioner Cheyenne Haatrecht explains that she was ashamed of her dark skin colour for years and even denied that she was black. “You’re blacker than me, so you’re uglier. Those were very normal statements in my childhood in Suriname. Black is negative. We still talk about a black page, a black day. I don’t use those kinds of terms myself, but it’s very normal in the Netherlands. It doesn’t bother me, but it does bother people like this lady. And she’s really not the only one in the Netherlands.”

A few years ago, the Netherlands apologised for its history of slavery. What do you think about that?

“Quite rightly so, but I think we’ve got a bit stuck in the apologies. If you ask me, we should do much more research into the wider impact of slavery. Economically, for example, try to find out how much wealth was taken from Suriname during that period. Maybe we should give some of that back, to a foundation, for example.”

“But we also need to investigate the psychological impact of slavery more thoroughly. I once met a Surinamese gentleman in the Netherlands whom I advised to apply for a job at the university. He said, “No, because the white people won’t take me seriously.” I fell down in my chair when I heard that.”

Will you be celebrating Keti Koti this year?

“No, not this year. I find it a bit repetitive every year, whereas I think we should be moving in a different direction. I think we need to talk about the consequences of slavery, about why I have become who I am.”

Isn’t Keti Koti the perfect time to ask those questions?

“You can ask those questions, but it’s not the main focus. It’s mainly about celebrating and being happy with our freedom. I’ve been there several times myself, but my wife and I don’t really partake in the festivities.”

Do you think it’s an important day?

“It’s a very important day. Surinamese and Dutch people reflect on what happened during that period. I think that’s really important. So I certainly don’t want to dismiss the celebrations, but I’ve heard the issues being discussed many times before.”

Are you hopeful about the direction we are heading in?

“Yes, I also think that the Surinamese community has become more vocal about certain issues in recent years. Black Pete (Zwarte Piet), for example. But there is too little discussion about how we should solve the existing problems. In countries where many descendants of slaves live, we do not see an immediate improvement in their position.”

“In the Netherlands, incomes and social services are good, but many black people still feel blocked in some way. Look at the intellectual who doesn’t want to apply for a job at the university, or the police commissioner who denies her skin colour. I think that barrier can disappear, it has to disappear, but it will take a very long time.”