Papuans as foster children with Dutch families: generosity or colonialism?

In the nineteenth century, a group of religious idealistic couples travelled from Holland to New Guinea to adopt and re-educate local Papuan children. The missionary couples were full of good intentions, but how noble was this civilising and converting really? Historian Geertje Mak wrote a book about it.

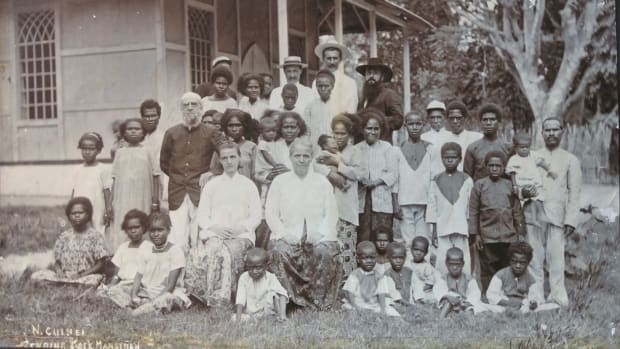

‘Mother of Papua’. This text adorns the grave of the Dutch Wilhelmina van Hasselt, who died in 1906. She ran a large household on Papua, taking in several foster children she had freed from slavery. In a photo from 1902, the couple sits pleasantly among all their foster children-and adults.

The Van Hasselt couple were not the only couple who cared about the local population of New Guinea. They were part of a group of Dutch missionary women and men who settled on the north coast of New Guinea from 1863. The aim: to civilise the Papuans who lived there and convert them to the faith. Gender historian Geertje Mak wrote the book ‘Household in New Guinea. Mission and the colonialism of good intentions' about this colonial re-education project.

Gratitude

Was it all really as peaceful and well-intentioned as was suggested? And did the Papuans, including the re-educated children, actually feel like this Dutch interference? “The enthusiasm to do something for someone else was very much alive in the nineteenth century,” Mak says through Zoom in an interview on her book. “But of course it was based on the idea: we are going to tell the people there how they can live better and become Christians. Such a civilisation mission and wanting to do good went hand in hand back then.”

Thinking that we can help other people develop is still not foreign to our Western world, Mak says. According to her, that is exactly what the book is about: the desire to want to do good and give something to the other person, in exchange for gratitude. In Holland, for instance, money was collected for Papuan children in the nineteenth century. “That went a long way,” Mak says. “For example, there was a donation box in the shape of a little black child, whose belly had a text saying “thank you” and whose head nodded gratefully when money was thrown in at the top.”

Meanwhile, there was intense writing from New Guinea about the missionaries' efforts. ‘Joosje freed, a most lovely child,’ Wilhelmina van Hasselt wrote in a letter. ‘Hindoe, 6 Jan 18 freed from own means, then 14 years old, malnourished and on the brink of the grave and emaciated, now by our Lords Grace a bright cheerful girl.’

(Text continues below image)

A possible quid pro quo for donations to the mission was to name the ransomed child after the donaters. Mak gives the example of a child being named Deventer, after the anonymous giver from Deventer. Another child is named Utrecht, to thank the anonymous non-mediated givers of a Sunday school in Utrecht.

“This symbolic appropriation of the ‘freed’ children through a new naming is strongly reminiscent of the practices from the earlier Dutch slave trade and slavery,” Mak writes, “in which enslaved people lost their own names after being sold and had new ones imposed on them.”

Passing on children

Letters to the motherland often described the most wretched cases. “Sometimes children had been taken from very violent, horrible conditions and found peace with the Dutch families,” says Mak. “If you look superficially, you think: these children were saved by the missionaries. But if you study the sources more closely, you notice that a boy or girl is suddenly mentioned with another family. So the foster children were also passed on or taken to Europe quite easily. Moreover, it seems that Papuan children did not eat at a table together with Dutch children and also slept somewhere else. These are small differences that stand for something bigger.”

Once released by the missionaries, the Papuan children were baptised, given Christian names and enjoyed education together with local Papuan children. Moreover, they were employed in jobs such as building, cultivating land and household chores. “There was this idea that Papuans were some kind of children, to be raised to independence by the ‘motherland’,” Mak writes.

This was not without controversy. Mak: “A big misunderstanding between the missionaries and the Papuans was about freedom. The Dutch missionaries bought the Papuan children free and trained them in, for example, cultivating land, with the idea that later they could provide for themselves. That was freedom.”

“To the Papuans, on the contrary, individual autonomy was totally unimportant, on the contrary: you are only important if you have a lot of relationships and a lot to give away,” says Mak. “They knew a gift economy: you give away food and clothing, which makes people owe you something and therefore gives you a certain power. The Papuans despised slavery. For them, freedom meant that you cannot let someone else tell you something. If you don’t want to do something one day, you don’t do it. Even their own slaves adhered to this principle. The foster children had to work in the garden: in the eyes of the Papuans, that was slavery.”

Scrappy houses

Other problems were cultural. Papuans travelled around a lot and therefore often lived somewhere temporary. Their houses were built accordingly. This irritated the Dutch. They thought the Papuans’ houses were rickety. “A Papuan also calls a pigpen a house, likewise a nest, hanging from a tree”, says a letter Mak quotes, written by missionary Jens in 1890.

How did it end with the Dutch missionary on New Guinea? Around the time of Wilhelmina van Hasselt’s death in 1906, a smallpox epidemic was also raging on New Guinea. “The missionaries managed to vaccinate part of the population, who survived the epidemic,” says Mak. “And that caused a huge turnaround in the willingness to be converted. New missionaries in the following decades ensured a new phase and the fact that New Guinea is still a very Christian country today.”

Today, the old ideal of turning a so-called ‘natural people’ into a ‘cultural people’ is under fire. “The capitalist exploitation of the earth is now under discussion,” says Mak. “Now the Papuans’ way of life is seen as an example perhaps, from which we can now learn something the other way round.”

Geertje Mak, Huishouden in Nieuw-Guinea; zending en het kolonialisme van goede bedoelingen, (Walburg Pres, 2024). Prijs: € 29,99