Realistic AI videos pose a threat to democracy, warns UvA researcher

More and more often, lifelike fake videos created by AI are popping up online, including some that appear to be set in the Netherlands. “In some cases, fake is indistinguishable from real,” says UvA researcher Laurens Naudts. According to him, this uncertainty undermines not only trust in these videos, but also in democracy itself.

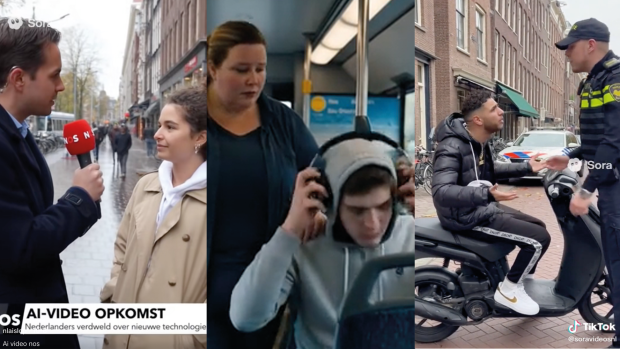

A woman being ridiculed on a GVB bus. A police officer fining a frustrated scooter rider. And a NOS reporter interviewing someone about ‘the increasing number of videos being made with artificial intelligence’. Ironically, while ‘he’ warns about the rise of AI videos, he himself is the product of artificial intelligence (AI).

But this NOS AI reporter is right; you can increasingly encounter realistic-looking videos generated by AI online—including those set in an apparent Dutch context, emphasizes UvA researcher Laurens Naudts of the AI, Media & Democracy Lab and Institute for Information Law.

More and better AI videos

Naudts is researching how to protect society from the increasingly difficult distinction between non-artificial and artificial content. “There is an emergence of AI models that can create text, image and video that are widely available to the public,” says Naudts, “which means you encounter AI videos more often on your social media timeline. In some cases, fake can no longer be distinguished from real.”

Most of the AI images you encounter online today are created with Sora 2.0, which is part of the OpenAI company and therefore has the same creators as ChatGPT. It is an AI program that can generate a video in no time based on the assignment you write. With real people: Sora can mimic the body, voice, and movements of real people based on video data used to train the AI model. Last month, Sora received a major update. With the Sora update, you can now create ten-second videos with music, sound effects, and even voices.

There is one striking thing, however: if you ask Sora 2.0 in English to imitate English-language media, it refuses. But if you write in Dutch, the video generator can suddenly create images that are barely distinguishable from a real NOS reporter, reports BNR. It is not clear why there is a difference depending on the language of the requester.

Risks

According to Naudts, the rise of hyper-realistic AI videos brings with it a series of social risks. “The realism of those images increases their persuasiveness,” he says. “That makes people more vulnerable to deception, manipulation, and even fraud.”

One concrete risk is fraud through the imitation of well-known individuals. “For example, you could replicate someone’s voice and appearance to create a deepfake in which that person asks for money,” explains Naudts. “Imagine receiving a video message from a family member who appears to be in distress and urgently needs money. The realism of the images may make people more inclined to fall for it.” In addition, realistic deepfakes of someone could be used to bully or sexually harass them online, says Naudts.

With just a few clicks, you could also create a video in which a newsreader, politician, or well-known Dutch person says something they never actually said in order to mislead or manipulate the public. “You could imitate the style of the NOS Journaal news program and its presenter to spread disinformation, for example about migration and asylum, and thereby influence public opinion or sow division,” says Naudts. Last week, for example, images circulated about the alleged arrest of former GroenLinks-PvdA party leader Frans Timmermans for subsidizing action groups to lobby the EU for his plans. These images were posted on the political Facebook page “We will NOT report Geert Wilders.”

Although hyperrealistic images can increase the risk of deception, Naudts emphasizes that even less convincing or even obviously fake images can have an effect, precisely because they evoke emotions. “I myself saw AI images from the PVV in the run-up to the elections. AI images had been created of a future Netherlands as a ‘caliphate’,” says Naudts. “Such a video does not have to be truthful to convey a certain sentiment or political message.” According to him, this shows that it is not only hyperrealism, but also the intention and emotion behind the images that determine their social impact.

Shaky trust

The fact that AI videos are becoming increasingly realistic not only affects what we see, but also how we trust, says Naudts. “In a democracy, we assume that citizens can assess information and form an opinion based on that. To do so, you need to be able to assess where that information comes from and whether it is reliable. If that distinction between real and artificial becomes blurred, that trust can be shaken.”

According to Naudts, this mistrust affects not only the media and institutions, but also people themselves. Inspired by political philosopher Mark Coeckelbergh, Naudts says: “When you are no longer sure whether something is real, you start to doubt your own judgment. Ultimately, this can lead to people speaking out less or participating less in public debate.” This could weaken the foundations of democracy because citizens become less informed and less involved in public debate.

Naudts also warns against the danger of everyone mistrusting every AI video upfront. “Not every use of AI means that something is untrue, and not every ‘real’ video tells the truth,” says Naudts. We must prevent people from reflexively rejecting everything that is made with AI. “The point is that people should be able to know what is reliable and continue to trust quality journalism and institutions that verify their sources.”

1. Look for the watermark. You will see “Sora” on videos made with Sora. Sometimes social media platforms themselves add an “AI-generated” label.

2. Pay attention to the details. In the viral video of rabbits on a trampoline, two rabbits merge into one as they jump. There are also incorrect shadows, strange reflections, and AI struggles with the fact that humans have five fingers.

3. Look at the time stamp. In so-called ‘security camera’ footage, the clock in AI videos often does not actually tick.

4. Listen carefully. Voices sometimes sound flat or unnatural, with incorrect intonation or mouth movements that do not match.

Protection

To protect yourself against realistic AI videos, simply warning that you are watching a video generated by AI is not enough, according to Naudts. “Citizens must have access to tools and knowledge to understand what they are seeing: where a video comes from, what information the AI model has used, and for what purpose AI has been deployed.”

That is why Naudts advocates for greater transparency from the creators of AI systems and for enabling a stronger journalistic watchdog function. “People must be able to rely on editorial offices and public institutions that fact-check and provide insight into how something was created,” he says. To make that possible, according to Naudts, people should be able to gain insight into the origin of AI images, for example, which source data or models were used in their creation. Such openness would not only enable citizens to recognize misleading content, but also help journalists to better fulfill their monitoring role.

On paper, steps have already been taken to protect citizens from misleading AI content. The European AI Regulation, which will come into force in phases in the near future, aims to make the use of artificial intelligence more transparent and safer. For example, companies will be required to indicate when AI has been used for a video, for example via a visible watermark.

Positive use of AI videos

However, realistic AI videos do not always have to be a threat. Naudts talks about journalists in Venezuela who are unable to do their work freely due to repression by the Maduro regime. For example, journalists were imprisoned for asking critical questions about the government. Now the journalists have found a solution with AI. “There, AI is used to deliver news via digital avatars, so that reporters can remain anonymous,” says Naudts. “The avatars convey the warmth of a human presenter but protect the real creators from persecution or violence.” According to Naudts, such applications show that AI can also contribute to freedom of information, provided that its use is transparent and responsible.