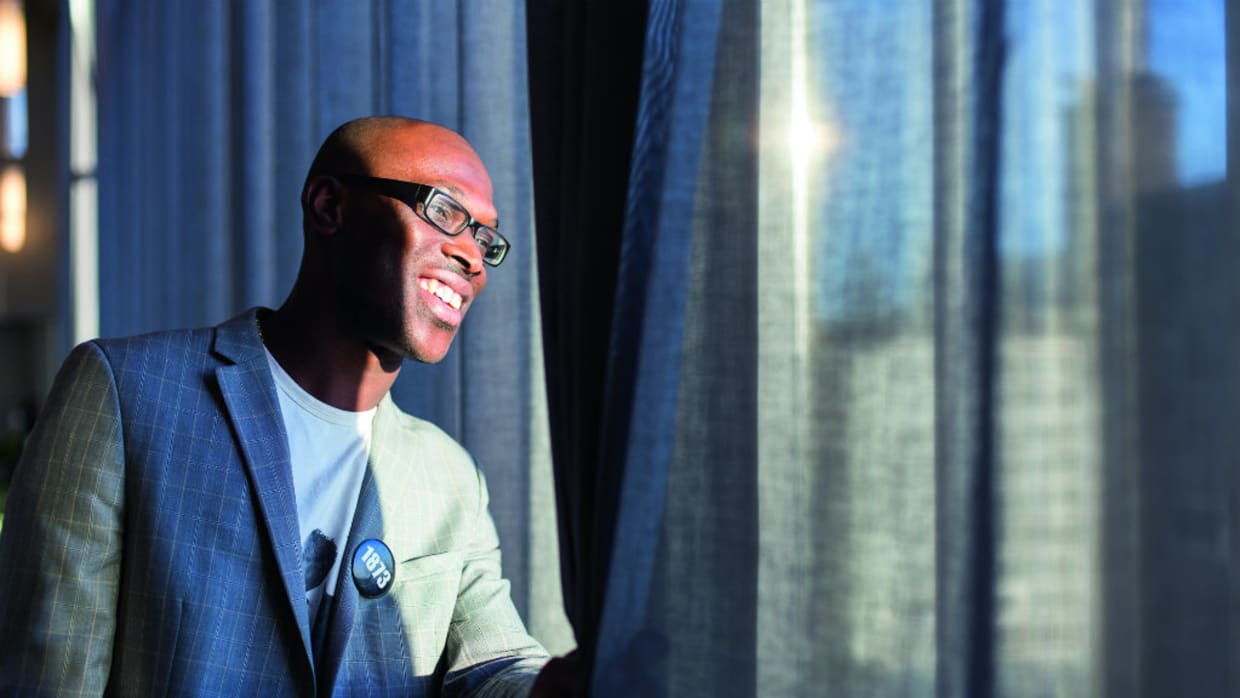

Later, finding himself in a 200-seat lecture hall at the Vrije Universiteit, a speck of colour in a sea of white, he began to seriously question his situation. ‘I started to read up on it and realised that it wasn’t me, it wasn’t my family – it was the system,’ says the academic coordinator at the UvA over a cup of tea, sat at his fifth-floor desk overlooking the Roeterseiland complex. ‘

A structural inequality between whites and non-Western minorities characterises the labour market,’ Esajas continues. ‘From first grade through to executive positions in business and academia.’ And he intends to do something about it.

Diversity and equality

Esajas is one of the trailblazers at the forefront of the movement for a more diverse UvA. Hours after he had addressed the crowds at the Maagdenhuis in the second week of this spring’s occupation, a new banner appeared on the monumental façade. ‘No democratisation without decolonisation’ it proclaimed. Partly through his work, the negotiations between the occupiers and the university board will not only yield research commissions on finances and democratisation, but also a group of four experts to explore the theme of diversity. ‘If all goes well, they’ll start before the year is over,’ Esajas says with some satisfaction.

On his own role in securing these results, he remains modest – but ask anyone at the university who to talk to on matters of diversity and equality, and they’ll point to the 27-year-old with the shaved scalp and the infectious smile. All right, he admits, so he does have quite some experience where diversification and decolonisation are concerned. In addition to his work as president of the New Urban Collective, an organisation that he co-founded that connects young people of non-Western backgrounds to potential employers, he uses his own experiences to educate and advise.

Esajas is well aware of the problems students of colour have to face; issues that their white, Western fellow students often remain completely unaware of. ‘It starts with that feeling of being one of the few darker-skinned people in a sea of white,’ Esajas says. ‘You have very little social capital, meaning you know few people with a university education whom you could ask for help. The curriculum you’re taught contains nothing but texts by white men from Europe and the United States, while outside of class you experience institutionalized discrimination and stereotyping.’

Slavery

What causes this? Esajas points to his left lapel meaningfully where he sports a badge with the year 1873. ‘The abolition of slavery,’ he explains, ‘the official date is 1863, but the slaves had to do unpaid labour for ten years after that – hence 1873.’ Those who think that the world has put colonialism behind it are very wrong, he says. He believes the current inequality at universities is closely connected to slavery in the past.

Esajas’ activism is mirrored in a broader movement of students worldwide that have taken to the streets this past year in several countries. This spring, students in Cape Town made international headlines when their protests led to the removal of a statue depicting Cecil Rhodes, a symbol of British colonial presence in South Africa. Currently, students at Oxford University – boasting a Rhodes statue of its own – are attempting to do the same. In the US, protests are even more vehement. Earlier this month, the president of the University of Missouri resigned after a black student had gone on a hunger strike amid accusations that the president had not suffi ciently acted against racism on campus.

‘Whether it is in the US, the UK or in Africa, the different movements are one at their core,’ Esajas says. ‘The movement seeks to show how much of an impact four centuries of history have on the way that knowledge is produced. Western culture was seen as superior for hundreds of years, while blacks were depicted as primitive.’ It is high time to finally decolonise the university, students feel. High time too to acknowledge that – not withstanding former colonies’ political independence – that the colonial past still affects the present in many ways.

‘It’s very apparent in knowledge production in an all-white curriculum, but also visible in our cultural traditions such as Zwarte Piet [Black Pete, the traditionally black-faced servants accompanying Saint Nicholas in the Netherlands], in the lack of diversity in the media, the labour market and in executive positions.’

Colour blindness

While other Dutch universities, such as the VU, Erasmus and Leiden University, have actively implemented policies to enhance diversity, the UvA has chosen not to. ‘An often heard excuse is “We don’t discern between ethnicities or backgrounds” – the politics of colour blindness. It’s a noble thought, but it also denies part of our social surroundings, part of reality.’

That not everyone feels welcome at the UvA was demonstrated last year when student organisation Amsterdam United launched #ITooAmUva, a campaign against so-called micro-aggression: remarks that seem commonplace, but that can be found hurtful. UvA students of different ethnicities were pictured in a photo series, holding up signs with sentences such as ‘Your Dutch is really impressive!’, ‘Where are you really from?’ and ‘What, you study at university?’

Esajas has been at the receiving end of such remarks, too. ‘“I bet you’re an excellent dancer”, they’ll say.’ And no, of course no offense is meant. ‘But that doesn’t matter.’ In matters like racism, discrimination and exclusion, it is not so much the intention, but the result that counts, Esajas says. ‘When I accidentally drive my car over your foot because I’m not paying attention I might not have meant harm, but at that moment it doesn’t help you much.’

It is essential to create awareness of these subtle forms of exclusion, as well as of our own prejudices, Esajas stresses. If it were up to him, diversity policies would already be introduced at primary school level. To hear about the subject only once one arrives at university means quite a late introduction to a complex set of problems. Still, he feels the universities should take lead. ‘The university is a societal role model. People look up to the institution as a beacon of science, a fount of knowledge.’

Fundamental change

As for the future, Esajas is cautiously optimistic. ‘I think we’re heading in the right direction,’ he says. ‘When I look around me, I see this new consciousness, this wave of activism around the world – and not just within the black community, but more broadly.’ He recounts how, recently, he came upon some Zwarte Pieten in the UvA dining hall. ‘By the salad bar, behind the sandwich counter, at the soups – there were boxes wrapped as presents in Black Pete wrapping paper everywhere.’ He wrote a caustic, 1200-word letter to the university’s press bureau, facility services and catering employees. The very next day, the offending packages were removed and apologies offered. ‘That’s a fundamental change,’ Esajas says contentedly. ‘Had I done this five years ago, I probably would have been told to stop whining.’