Marie du Saar (1860–1955) was the first woman to earn a doctorate at the UvA

Marie du Saar (1860–1955) was the first woman to earn a doctorate at the UvA and the first female medical specialist in the Netherlands. Yet her name has almost disappeared from the collective memory, and many misconceptions about the scientist persist. Historian Tineke van Loosbroek aims to finally do her justice with a new biography.

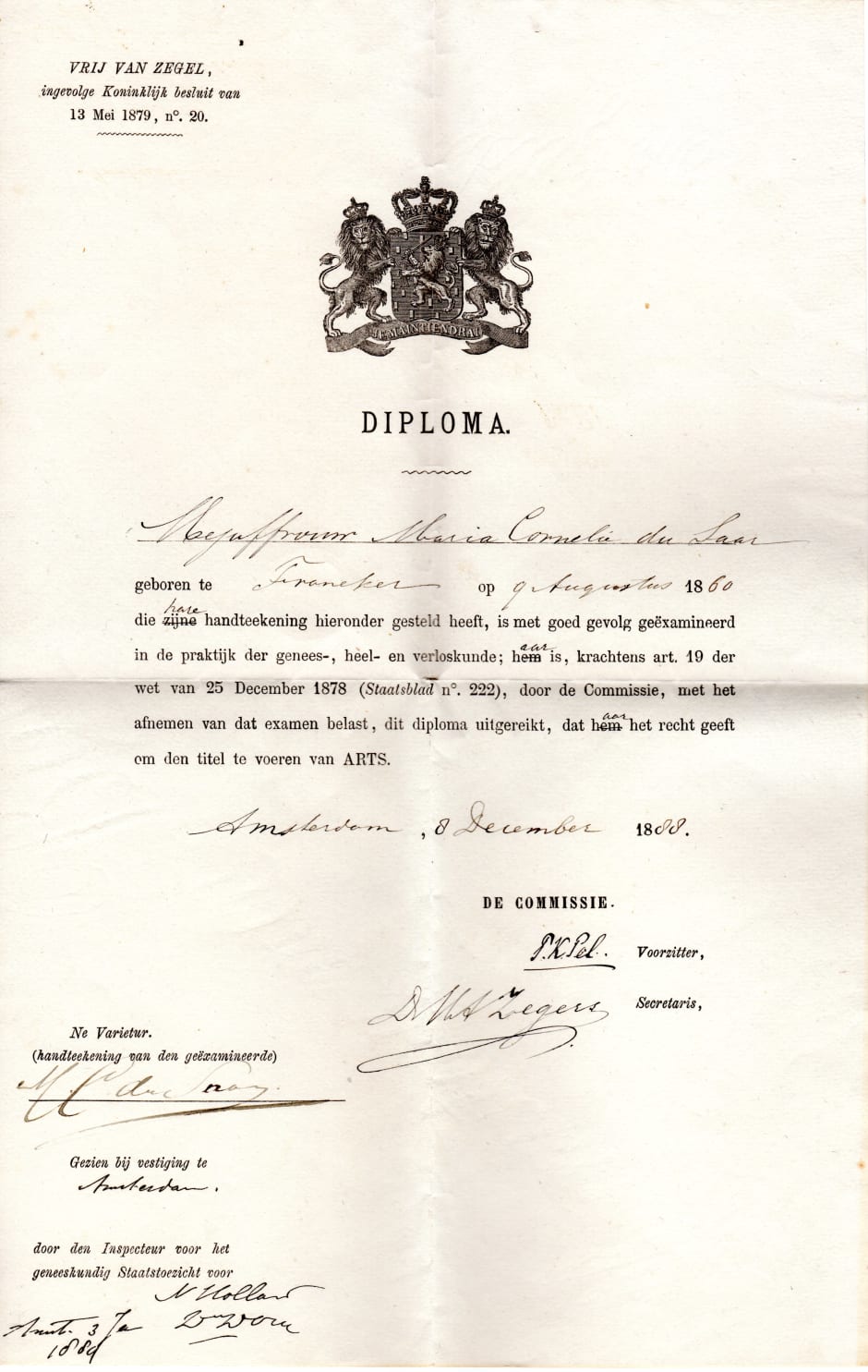

On March 28, 1890, the very first woman earned a doctorate at the UvA: Marie du Saar. The interest was so great that part of the audience had to remain standing in the hallway. Not surprising: a woman earning a doctorate – cum laude, no less – was truly exceptional at the time.

What must it have been like for Marie (1860–1955), the only woman among men at the medical faculty? And why did she fade into obscurity? It certainly wasn’t because she gave up her career after marrying, as is often claimed, historian Tineke van Loosbroek discovered: Marie du Saar worked for nearly ten years as an ophthalmologist in a male-dominated field. Van Loosbroek wrote about it in the recently published Dutch book From Pioneer to Outsider.

A respectable lady

Van Loosbroek describes how Marie’s doctorate crowned years of struggle and perseverance. “She was incredibly determined,” Van Loosbroek says. “In her youth, the family suddenly ran out of money after her father left for South Africa. And this was despite coming from a fairly bourgeois family. That drove her; she wanted to belong to respectable society and to be a proper, respectable lady.”

For a long time, Marie du Saar was the only female medical student. She was also the first in her family to attend university. Among all the male students, she stood out as an odd one, Van Loosbroek writes in the book. “‘I still see you as a lone figure among all those unruly lads in the lecture halls—partly admired for your courage, but also criticized in a narrow-minded way by many,’” a male fellow student wrote to Marie years later.

During an anatomy practical, she faced open criticism. “That Marie was there dissecting naked bodies was considered unladylike,” Van Loosbroek explains. “Not by the professors necessarily—they appreciated an intelligent, engaged, and interested student, even if it was a girl. But for the fellow students, it was different; there was still the element of competition.”

The University Library (UB) named nine meeting rooms after “forgotten women”: pioneers in medical science.

Ironically, Marie du Saar was initially overlooked. Following a tip from Tineke van Loosbroek, a tenth room is now being named after the first female doctorate graduate of the UvA.

Downhill

The professors, on the other hand, supported her. Marie maintained contact with many of them even after her studies. She chose to specialize in ophthalmology, “a respectable field”. But from there, things essentially went downhill, Van Loosbroek describes in her book. She married the musician Heinrich Hammer, a marriage that was far from a golden match.

She opened her own private eye practice, which she struggled to keep running. “There were too few patients,” Van Loosbroek explains. “Mostly women and children from Marie du Saar’s own network or her friends. Men went to male ophthalmologists. As a result, she earned too little to make ends meet.”

Eventually, she had to close her practice and followed her husband abroad. Her health grew more fragile, and her marriage to Heinrich did not last due to his fickle desire to travel. Marie and the children followed him to Germany and Switzerland, until she had had enough. Finally, in 1911, she returned to Amsterdam, even though the divorce was not finalized until 1924. Her doctoral degree and her past as a physician gave her a certain prestige, but she no longer practiced her profession. She is now past fifty, writes Van Loosbroek—an unemployed citizen, an outsider, a mother, and a housewife.

After a flying start, Marie comes to a halt. “She fought so hard in her youth to have a career, earn money, and be part of society,” Van Loosbroek says. “And then she was still pushed back into the home and family, into the position of outsider she never wanted to be. There is something tragic about that.”