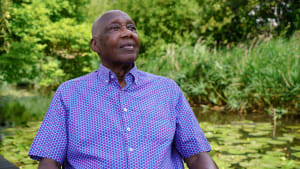

Professor Chan Choenni on Surinamese independence being “imposed”

During his childhood in Paramaribo, Chan Choenni (72) knew no different; Suriname was part of the Netherlands. But when the emeritus professor of history and Surinamese studies later moved to Amsterdam as a young man, he witnessed Suriname’s independence on 25 November 1975 as a student at the UvA. Fifty years later, he looks back.

It is exactly fifty years this month since Suriname became independent. At the time of your birth, in 1953, Suriname was still a Dutch colony.

“That’s right. In 1954, Suriname only became an equal constituent part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. That meant there was a certain degree of autonomy, but foreign affairs and security remained under Dutch control.”

“The debate about independence first flared up among a few radical nationalists in the Netherlands; in Suriname itself, the issue wasn’t particularly pressing at that time. Later, fierce discussions broke out in the country, because a large part of the Surinamese population opposed independence. The problem was that there was also a very active, vocal minority that supported it. Moreover, it fitted into the global trend of decolonisation. The Netherlands wanted to rid itself of its colonies for the sake of its reputation.”

So you’re saying that most people in Suriname weren’t eager to become independent?

“Indeed, the majority was against it. People in Suriname were generally very loyal to the monarchy and wanted to remain part of the Netherlands. There was a small but vocal group pushing for independence, but they were in the minority. The Dutch went along with it because they wanted it themselves. Independence was imposed. It came too soon, and the population wasn’t ready for it.”

How was the topic viewed during your youth in Suriname?

“In the 1950s, Suriname was modest, but during the 1960s prosperity grew, and the country made progress. Relations between the different ethnic groups were good, and Suriname was among the better-performing nations in South America. But when, at the end of the 1960s, a leader came to power who strongly supported independence, polarisation began. The Netherlands encouraged that development.”

And by doing so, the Netherlands plunged Suriname into a period of uncertainty?

“Yes, the Netherlands declared Suriname independent during a highly uncertain situation. Three billion guilders were gifted, but the money ended up in the wrong hands and was poorly spent.”

In 1972, three years before independence, you moved to Amsterdam to study at the UvA. What was that like?

“At that time, the Netherlands was very left-wing. I wanted to become a police inspector, but people told me that was a very right-wing, bourgeois ambition; definitely not something to aspire to in those days. It was also the era when terms like ‘Third World’ and ‘decolonisation’ were emerging: the hippie years. I was swept up in that wave. I studied political science and philosophy of science, and I thoroughly enjoyed my student life in Amsterdam.”

As a Surinamese man, were you something of an exception at the UvA?

“No, quite a few Surinamese had traditionally come to study at the UvA; it was something of a hotspot. Professors often remarked that Surinamese students generally performed very well. We had a solid reputation. And since I had grown up in Paramaribo as a Hindustani, I was already used to being part of a minority group. That helped me to relate to all sorts of people. I was completely accepted and never experienced discrimination at the UvA. I was well liked.”

Was there already a debate at the UvA at that time about decolonisation?

“Definitely. It was the most leftist period imaginable, so everyone strongly supported Suriname’s independence. People believed Suriname was being exploited and needed to be liberated. Those discussions were common. There were many students at the UvA campaigning for Surinamese independence.”

But you were against it.

“Indeed, I was not in favour of independence, because I believed Suriname would fare better with Dutch support.”

It ended up happening anyway. How did the Surinamese community in Amsterdam respond?

“Some were pleased, as Suriname was now free. But others didn’t believe in that future. I was among the latter. I sometimes voiced that opinion, but you were quickly drowned out by those in favour, so it didn’t make much difference. What’s interesting, though, is that many of the people who had loudly demanded independence eventually ended up staying in the Netherlands. They were very vocal in their opinion that Suriname had to be free, but they never went back to help rebuild the country. There’s a kind of ambiguity in that, they didn’t want to make the effort themselves.”

Did attitudes towards Surinamese people in the Netherlands change after independence?

“At first, our reputation worsened, because many young Surinamese men came to the Netherlands and ended up in drug-related crime. There was a lot of cannabis use and public nuisance. So there wasn’t an immediate emancipation of Surinamese people in the Netherlands, that really only began in the 1990s. At that time, more jobs and housing became available, and successful Surinamese football players played an important role too. After the Dutch national team won a match, I’d suddenly be embraced and seen as a fellow countryman. In later years, public attention shifted towards Islam and Muslims, which allowed Surinamese people to continue integrating quietly.”

You ended up working for the universities of Leiden and Utrecht, and eventually became a professor of Surinamese studies at the VU. Over the years, increasing attention has been paid to the colonial past in academics; the UvA is now even researching its own role in it. How do you view that?

“That topic is becoming increasingly important. Understandably so, since a quarter of the Dutch population has a migrant background, and in the major cities that’s even half of the population. But although colonial history is now taken more seriously, the proportion of students from migrant backgrounds at the UvA is still lower than at, for instance, the VU. That’s an interesting phenomenon.”

Why do you think that is?

“I think the VU, due to its Christian roots, traditionally fostered a friendlier atmosphere towards Surinamese people, as well as other religious communities. The UvA, on the other hand, especially within the social sciences, has always had a left-wing profile, and thus mainly attracted left-wing students.”

So even fifty years after you studied there as a young Surinamese man, there’s still work to be done at the UvA when it comes to emancipation?

“Yes, the emancipation of minorities, migrants, Surinamese – whatever you want to call it – in that respect, the UvA still lags far behind other universities.”