Read back | Bob (100) was Folia-editor in 1949: ‘Back then, it was just a very boring magazine’

Retired Amsterdam chemist Bob Dickhout is the oldest editor Folia has ever had. He recently turned 100. In 2018, Folia interviewed him about his time on the editorial board, where he was active as a student editor between 1949 and 1952.

“My student days began in 1945. I had already taken my final exams in 1943, in the science subjects of the gymnasium, but if you wanted to study, the Germans required you to sign a loyalty declaration. You simply didn't do that. Luckily, my rector was a good guy: I was allowed to retake my finals, this time in all the humanities subjects. German, French, and Latin and Greek. Those real philosophers—I actually found it all quite interesting.

“After the Second World War, I wanted to study chemistry and biochemistry at the UvA. I lived with my parents—that’s how things went back then—and I joined the Amsterdam Student Corps. That appealed to me. I ended up in the intellectual society A.E.G.I.S. and got introduced to Propria Cures. That was a scandal sheet made by some friends of mine—P.C. also announced the founding of Folia Civitatis. Later on, we got Folia delivered to our homes weekly, brought by the delivery service of the Clausen printing house. You did have to be a member of the ASVA student union, but pretty much everyone was. It was important to check Folia: for the announcements, the sick professors, and there was a list of graduates. You really had to read it.

“In 1949, Folia’s second year, the editorial board asked me to join as a student editor. By then, I was chairman of my society at the Corps and secretary of the Amsterdam Chemical Society, and it was widely known that I knew how to make myself heard. So I said yes. At Folia, my job was to ask scientists to write book reviews or pieces on their inaugural lectures. We also met every Thursday in a small office on the Prinsengracht to correct the galley proofs—we’d carry them there on our bikes, strapped under the carrier bands. It was a fun time, you know. We didn't have to rush to graduate at all, so I took all sorts of extra classes: Italian, Spanish. Really, the most enjoyable things.”

Raging Catholics

“It might sound like a life of luxury, but make no mistake: we were all dirt poor. In old copies, you can see that Folia also listed the daily specials at the student cafeteria: fried meat cutlet, pea soup, vanilla custard—a whole meal for just 1 guilder. In those days, there were almost no student jobs. Only around Christmas could you sort mail at the postal services at Central Station, which earned you 4 guilders an evening; that felt like quite a fistful of cash. So, Folia was also important for the perks: we’d read about the latest film at Kriterion—you could go there for 15 cents—and the cheap student seats at the Stadsschouwburg theater. I often “skimmed” the scientific articles diagonally, from top left to bottom right. Those were usually only interesting if they were about your own field.

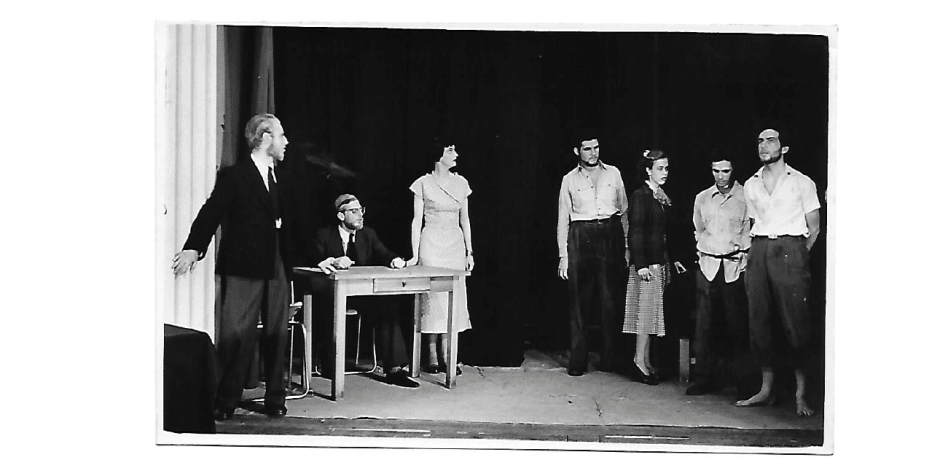

(Text continues below the image)

“I hardly ever wrote anything myself; that was for the “learned” folks. I’m not really a writer; I’m quite an active person. I did write a book review once, though, of The Mechanization of the World Picture, about physicists and mathematicians—wonderful, getting such a thick book sent to your home for free. I typed up the copy at home on my typewriter because Folia only had a very small office. So, we held our meetings on Mondays at Mrs. Warendorf’s house; she was on the editorial board as an alumna and was the wife of the then editor-in-chief of Het Parool. That was lovely; we got coffee and biscuits.

“I also once wrote a piece about a Swedish study on artificial insemination that used students—one of them already had fifty offspring. I added: “Perhaps this is a nice line of work for a working student. For customers, you should simply report to the leader of our Catholic People’s Party, Mr. Andriessen.” Well, then I had the whole Catholic community coming down on me, even though the editorial board had thought it was great. So, we had to apologize. The Catholic students even submitted a motion of censure to the ASVA members' council, but the majority there consisted of A.S.C. and A.V.S.V. members—my buddies, basically. The motion was voted down, haha. I didn't really mind it all that much.”

The first issue of the ‘scandal sheet’ Propria Cures (loosely translated: ‘mind your own business’) appeared in 1890. In 1948, Folia Civitatis was conceived as an independent publication for the academic community. To save costs, Folia and Propria Cures were squeezed into a single format for years, and the editorial boards had to correct their page proofs at virtually the same time. The editors of the two papers didn't care much for each other: the Folia editors considered P.C. to be printed on the back of Folia, while P.C. claimed the opposite.

Student days

“Ultimately, Folia was just one part of my student days. During the day, I often had practicals—with bacteria, for example—in the old laboratories at Roeterseiland and on the Mauritskade. We would set up a bacterial culture, and in between, we played ping-pong, because it took a long time before you could read the results of a culture like that. In the evenings, I would study, or I would be at the society: playing bridge, poker, talking a bit. It would be four in the morning before you knew it. The next day, my mother always woke me at eleven-thirty, because my father came home for lunch at twelve—that was just normal back then. I did have to pass an exam every now and then, of course. Incidentally, those were often oral exams, simply at the professor's home, very different from how it is now. Nowadays, the university is like a factory, and the standards have become much lower: there are 30,000 students, 20,000 of whom don't belong there, I always say.

“Student associations have changed, too. We got along very well with one another. Yes, during the hazing period they tried to put those smart kids in their place a bit, but it was mainly psychological humiliation. You had to crawl, and you were treated like an inferior product, but after three weeks you were already allowed to sit on an "easy chair." The staff at the society—usually ex-marines who knew how to handle authority—all knew your name by then and addressed you as 'Sir.' There was much more social hierarchy back then. Personally, by the way, I don't care for that at all.

“It wasn’t as if we talked about girls all day. It took a long time before you kissed someone anyway, and then she usually initiated it. I often had beautiful girlfriends, but I considered myself an ugly boy. Eventually, I was married for a short while—unfortunately to the wrong one. But well, if that was the worst mistake of my life, things aren't too bad.”

Vanity

“In total, I served on the Folia editorial board for three years. When I turned 31, I thought: now I really have to buckle down with my studies, otherwise I’ll end up a failure. Later, I heard that Folia was facing financial shortages and would only appear once every two weeks. Later, even just once a month. P.C. wrote a nice piece about that. I am actually still a subscriber; the new issue is lying on the table over there.

“If you had been a Folia editor, you received a bound book containing the entire Folia volume at the end of the year. Look, I’ve kept everything with my name in the colophon. That’s the vanity. I thought the final paper editions of Folia were very beautiful—it mostly reminded me of the TV guide, with so much color and imagery. It looks much more interesting than it used to; back then, it was just a very boring paper. I’ve seen the website too; it’s all very modern.

“I did study for quite a long time, yes, but I had also chosen the longest study imaginable. And I made up for it all: it was a good reason to reach a very old age, haha. That way, all that knowledge doesn't go to waste.”

Bob Dickhout (100) is a retired clinical chemist and was a student editor at Folia Civitatis from 1949 to 1952.