The 'most liveable city' isn't liveable for all

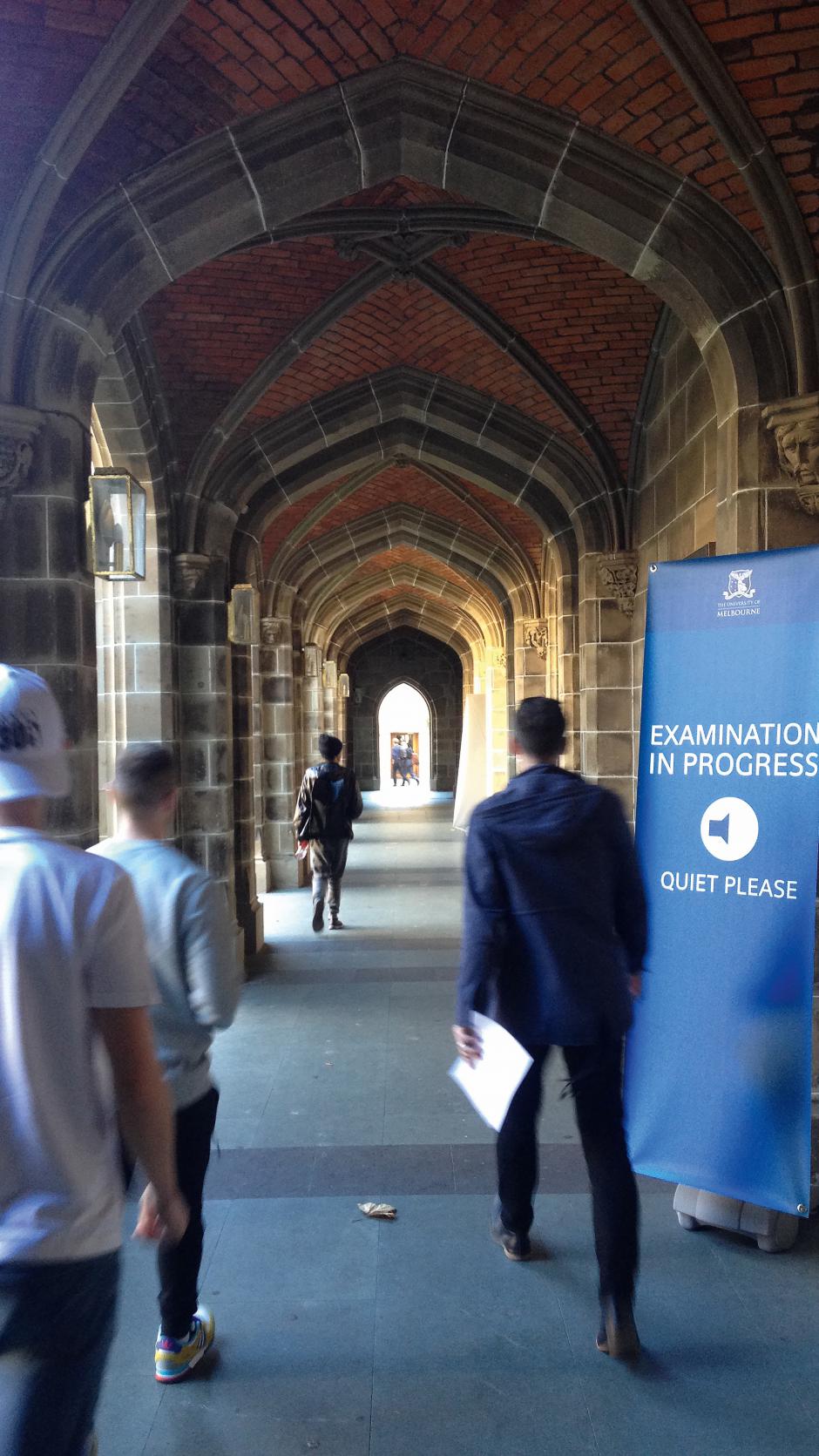

The most sought-after curriculum on the southern hemisphere, venerable cloisters, turreted towers and a campus sushi bar: the University of Melbourne has it all. Unfortunately, this all also includes very poor students, often sharing cramped rooms and scraping by just to pay for food.

One might expect Melbourne University, its main campus and student residences poised as it is on the threshold between the skyscraper shops and services of the Business District and the laid-back cafes of the northern suburbs, would barely need any amenities of its own. Apart from lecture halls and study spaces, what could a student seek that couldn't be found in what has been called 'the most liveable city' by the Economist for five years running?

And yet, ‘UniMelb’ boasts enough services and amenities to keep student life rolling on a remote mountain. Far beyond the classic campus pub or half-stocked stationary shop, students at Oceania’s most prestigious academic institution need never leave the tree-lined, cobbled campus grounds. Just ambling between the elegant residential colleges built after the Oxbridge model and enormous study halls, you’ll stumble across a swimming pool, a sushi restaurant, a crêpe stand, and two coffee shops to quench Australia’s national thirst for fl at whites. The Student Union building alone holds a hairdresser’s, a mobile phone store and a Japanese sake bar (with hundreds of varieties on offer), and it’s no problem if you feel like ice cream, patisserie, quality Mexican food, Italian, Chinese or eating vegan, or even to buy your groceries at the in-house supermarket and bakery.

But the emphasis is on the word ‘buy’. Out in the Central Business districts, every other restaurant has a homeless person on its stoop, and you can’t help but notice the Occupy tents in protest against the omnipresent 1% in its busy shopping square. With student fees around 8000 Australian Dollars, about 5000 Euros for a full academic year, many students are left with (very) tight budgets, indeed.

The result is that between the posters for the Trans Collective and techno parties splashed across campus walls, you’ll see advertisements for the weekly Free Student Breakfast for those who need it, accommodation assistance, and even a student-run food bank. Housing prices around the main campus are skyrocketing; most students can only afford to live in one of the venerable colleges on a scholarship. Invisibly but surely, the rift between haves and have-nots divides the student body as it does the rest of Melbourne.

A curtain for privacy

It's not a bad room, thinks Andy (22, business). Living in the centre, close to the university may be vastly more expensive than choosing from one of Melbourne's many suburbs, but 'part of what I would save in rent, I'd spend on public transport,' the Taiwanese student reasons. He shares a cramped room on the north side of the Central Business District with two other international students. It's not ideal, they agree, but since they spend most of their day on campus anyway, in libraries and classes, no one gets in each other's way much.

The house they share must once have been a charming, small family apartment by the looks of it. Set in a courtyard that would be in high demand among yuppies, one can still see original wooden paneling disappear behind a makeshift, hastily placed wall. These walls are a housing solution visible everywhere around Melbourne’s seven large universities: as in the tenements of nineteenth-century New York, landlords are finding creative ways to divide existing spaces up between as many tenants as possible.

Though Melbourne has no housing shortage to speak of, students are moving into these cramped, yet centrally located lodgings to be close to the university. Three, sometimes four to a room, with a curtain for privacy or even sleeping in converted garage boxes: comfort is not a priority when working towards an expensive degree at a prestigious university right on your doorstep. Quoc apologises for the smell in his tiny, screened-off downstairs bedroom: another housemate’s Southeast Asian cooking wafts in over the thin Paravent. The landlord does not allow photos to be taken.

Disadvantaged groups

It’s hard to imagine a starker contrast than between these apartments and those of students across the road, in Melbourne University’s residential colleges. Gothic windows, faux-medieval turrets and imposing chapels adorn their living quarters, even if the rooms themselves are nothing extraordinary. Still, a small single room in the Trinity college’s Edith Head hall, one of the cheaper options, costs almost 500 dollars a week, or around 1200 Euros a month. ‘I can only afford to live here because I have a scholarship,’ a passing history student ruefully remarks.

Outside Trinity, the dramatic stone clock tower is pealing the hour. Melbourne is of course far from unique in having part of its student population struggle. But they may feel particularly lost in a city seemingly built on haute cuisine, art and high fashion; on a campus with princely accommodation, cold drip coffee and a student magazine printed on glossy paper thick enough to sleep under.

‘As a university we are framed, in many respects, as this old, conservative institution,’ says Tyson Holloway-Clarke, (25, history), president of the university students’ Union UMHU. ‘But if you look at our student base, we really aren’t.’ Australia traditionally has had a vast lower and middle socio-economic class, Tyson explains. ‘This university attracts many people who want to improve their lot in life, and that of their families. Many of the students’ union offi cers come from backgrounds that make them understand what it is to be disadvantaged. Part of their passion is to ensure that people aren’t left behind. That’s certainly my perspective.’

Tyson rose through the ranks of university politics as part of the indigenous collective, and came to the university through its extensive access program for disadvantaged groups in the country. ‘In my family it was seen as a really big deal. I lived in indigenous communities all over the northern territory and several lower socio-economic working class towns in Tasmania before going to high school, and subsequently being fortunate enough to get academic scholarships. By the time I got to college, I had just about been to every socio-economic place you could be in this country.’

Students support students

The Student Union he now runs has departments representing women, indigenous and queer people, people with disabilities as well as offi cers organising activities and clubs. Luckily, they don’t have to work on a student’s budget as in addition to a small independent advertising and rental revenue, the Union’s funds are provided through the Student Services and Amenities Fee, a mandatory 250 dollars that students pay on top of their fees each year. About 40% of the 15 million collected goes to the Union. Much is spent on activities and clubs, but as the Food Bank and Free Breakfast posters show, welfare is an important part of the Union’s tasks. ‘As an organisation we fund and support whatever students want to do, and students here have a passion for supporting other students,’ Tyson says. ‘We’ve had liberal governments in our state for the past decade, which was pretty poor in its support for services and its welfare. Then the university scrapped a lot of services and student support and we’ve had to pick up where they left us. The federal government has been liberal since 2013, which means it doesn’t really support welfare stuff.’

The combination of the intense nature of studying at a top university, the casualisation of the work force, reductions in welfare, increasing costs of living and a decrease in accessibility to welfare is set against the fact jobs are harder to get, (‘and the ones you do get as a student are lower paying and insecure’, Tyson knows), are all major issues for these students.

And what about the students with ample funding, living in colleges and worried more about essays than where their next meal comes from? ‘I like to think that typically, as an Australian culture, we can politically swing different ways, but when faced with tragedy, unfairness or imbalance, we can be reasonable and empathetic and act according to that reality,’ Tyson states. ‘My own scholarship shows that prestige and elite success is not limited by your socio-economic status. People here appreciate that a university education isn’t a privileged elite good, but a means to elevate people. Even the right wing believes access to education is important – they just argue over where the money should go.’

Where government might be a little absent, the Student Union sees the value in investing money in support. ‘The difference between a student just scraping by and really hating their university experience, and one really enjoying it and getting the most out of their time and coming out well-positioned to go on to contribute to society could be as little as a few thousand dollars,’ Tyson says simply. ‘Be it through providing them with a space to study or a few free barbecues a year, it’s a sound investment.’