Sticking it out

Kyoto University’s trees blossom and its buildings gleam, but only some. Luxuries such as new dormitories are reserved for the international students it so desperately wants to attract. In the shadows, Japanese students live in incredible squalor. Why does the country’s richest university boast the poorest living quarters? And what goes on inside?

With spring comes the start of a new semester, and the road to Kyoto campus is lined with dozens of enormous, hand-painted signs. Featuring slogans and a considerable number of manga girls, they encourage prospective students to join the university’s many societies.

There is bowling, water polo and gymnastics; clubs for people who enjoy solving Rubik’s Cubes or composing comic haiku and, evidently, also enough enthusiasm to keep alive societies for Russian dancing, a doctors’ choir, butterfly appreciation and boomerang throwing. On the quad, four members of the tennis society are drafting new members. ‘We want at least thirty more,’ a girl wearing the official club track suit says spiritedly.

Joining a society, and rising within its ranks, is an intrinsic part of Japanese student culture, explains Michael, a 27-year-old neuroscience postgrad crossing the quad on his way from the lab. ‘You have to belong to a group and participate in extracurricular activities to woo future employers.’

‘It cannot be helped’

Diverse as the club scene may appear to be, it actually exemplifies Japanese conformist culture. As an old Japanese expression warns: ‘The nail that sticks out will be hammered down’.

But not all students at Kyoto are conformists — discontent is brewing just below the surface. With one economic crisis crashing into the next since the ’90s, the government has recently made controversial moves to restart the nuclear plants closed down in the wake of the Fukushima quake, while nationalism and militarization are on the rise under Shinzo Abe’s right-wing government. Besides these issues, the universities also suffered last year when a government decree forced many to cut their (supposedly less viable) humanities degrees. Yet students haven’t protested in serious numbers ever since the anti-Vietnam riots of the 1960s; a 2015 anti-militarism demonstration in Tokyo was criticised for resembling a high-fashion student street party.

Shikata ga nai the Japanese famously say when faced with adversity: it cannot be helped. Nonetheless, a small fire of critical thought and resistance to the seemingly inevitable forces transforming Japan still smoulders in some places, and Kyoto is definitely one of these. ‘The Japanese feel that social coherence is at the root of the country’s welfare. That’s why student activism here is so unique,’ says Michael.

Second tactic

Michael will not be joining any societies this year. ‘The social rules make it almost impossible; you’re expected to spend the weekends at the club house. I don’t feel like becoming a society president’s bitch,’ he laughs. In this, the Filippino scholar is illustrative of another serious issue for Japanese universities: for non-Japanese, the society scene is often too intense, a cause for the segregation of the international students Japan so desperately needs.

‘The country is facing declining birth rates’, Michael explains. ‘You might fi nd quite a few young people in Kyoto, but go out to smaller cities and the countryside and you’ll fi nd whole schools empty.’ To bolster the wobbling population pyramid, Japan tries to woo foreign academics like Michael. ‘Universities use two tactics. First, they’ve been trying to adapt its institutions to the Bologna Process. But the country’s low international rankings show how they fail at internationalisation even while their research is excellent — there is a Japanese Nobel Prize winner almost every year. Europe is much more shrewd at that game, with several countries taking up a single Erasmus student for a semester each, so a travel-thirsty student can earn two or three university internationalisation credits.

‘Kyoto University’s second tactic is over there,’ the postgrad says pointing, and leads the way to the sleek International Building, one that looks like the wrapping foil only came off the designer couches yesterday. ‘This is where we have Japanese lessons,’ Michael remarks as he passes: he has something much more interesting to show.

Riot police

Just behind the International Building’s shiny granite walls, the orderly campus grounds seem suddenly to end. Behind a few scraggly bushes, wooden shacks with broken windows rise from the murky shadows of a few forgotten trees. Chickens peck at the dry leaves in front of Yoshida Hall.

The ancient dorms of Yoshida are the last of its kind in Japan. Its dark timber walls must once have been magnificently beautiful before the university stopped maintaining the buildings and students took over. Here, an active — and activist — student body runs the laundry, a games room, yearly activities and sets the rent. Ancient cables hanging from the ceilings have provided Internet for a decade: left to fend for themselves by the University, all upkeep is performed by the students themselves.

The contrast painfully exposes Kyoto University’s uneasy inequality as well as its potential for student unrest. It was from halls like Yoshida, and the slightly more modern Kumamoto Hall nearby, that the student protests of the 1960s and 70s started, and universities throughout the country have since demolished these independent institutions and put students in apartments. Kyoto University tolerates these black sheep – shikata ga nai – but does so uneasily: the 2014 semester started with a bang as helmeted riot police stormed Kumamoto Hall. The raid was vaguely described as ‘a left-wing movement that may involve students’. Three students were arrested and subsequently released.

Das Kapital

‘They just wanted to break up a party we were having,’ scoffs Toyoma (30, chemistry), who has lived in Kumamoto for years. ‘Of the four hundred students here, maybe ten are real activists.’ Inside his hall of residence, a short walk away from Yoshida, students are making good use of each concrete-walled room: musicians practice their instruments and others hold swap-meets. They have to be efficient: the student council tries to provide as many students with (extremely) affordable accommodation (as low as 4000 yen, about 35 Euro a month) as the 1960s building can hold.

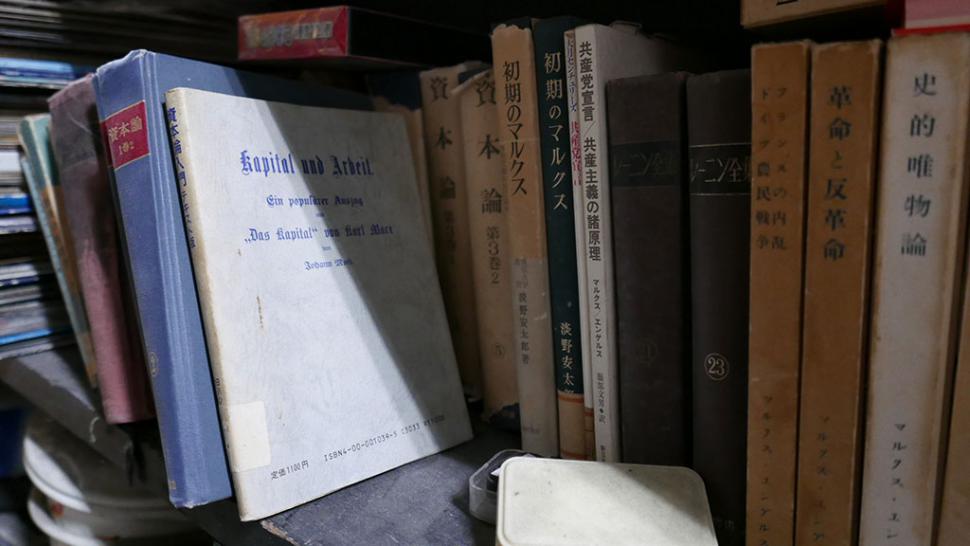

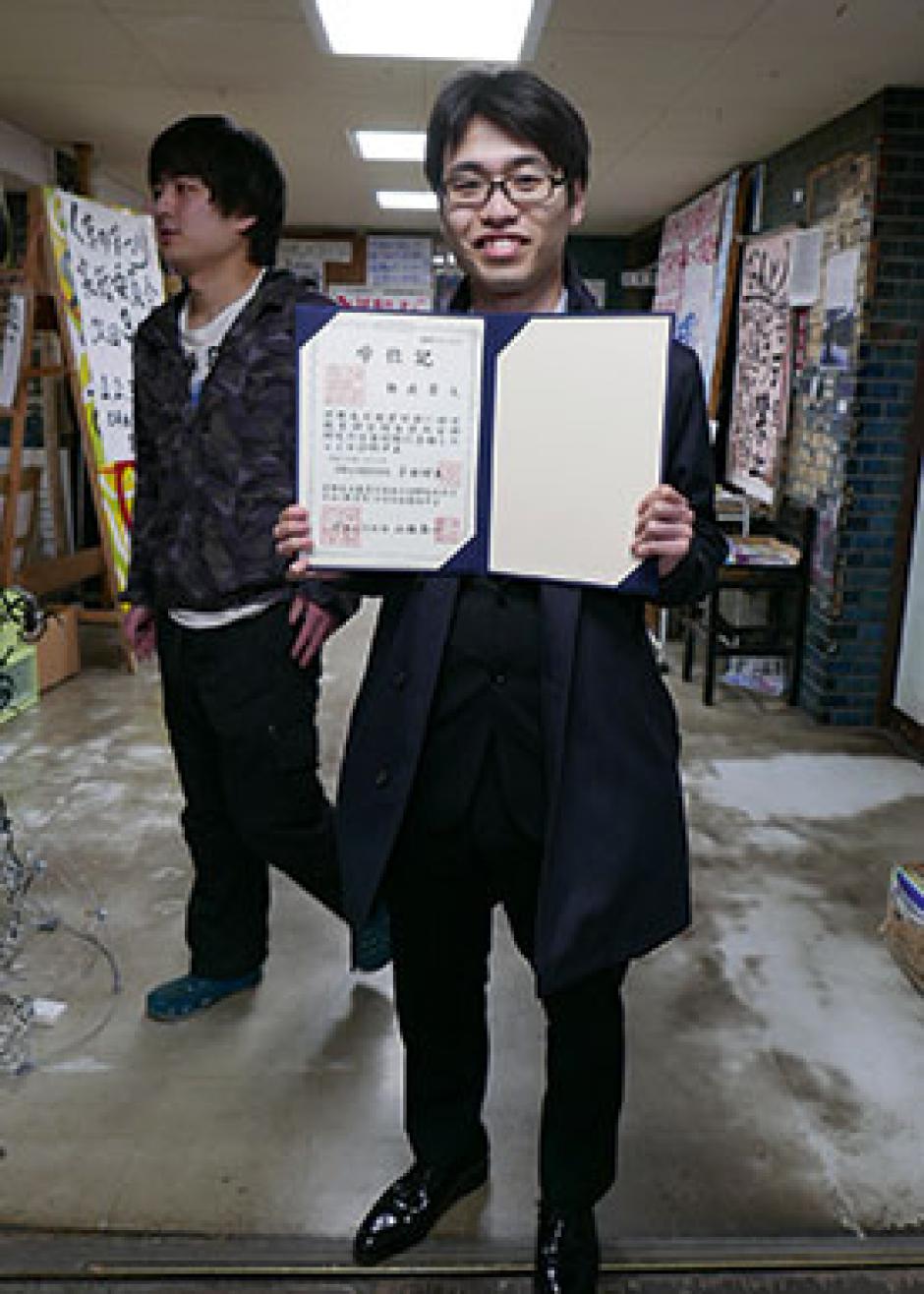

‘Each year, all residents gather to discuss Kumamoto’s and university policies,’ says Yosuke (30, mathematics), member of the Kumamoto student council. ‘For example, the university has been trying to evict residents as soon as they graduate. But we voted to let them stay.’ And although proper activists are indeed rare, ‘Kumamoto tends to function as a rallying centre for others around the university,’ he explains as he descends a stairway into a chaotic, cluttered basement. In the corridor, opposite a bookcase featuring Japanese-German books on socialism (including Marx’s Das Kapital) he points out a heavy metal door. ‘If a council meeting is held behind there, no police can enter,’ he remarks dryly.

Student activism

Inside, a few chairs are tucked neatly under tables holding two ancient computers. It looks mundane to the extreme. Yet this basement bunker could be considered one of very few hearths of student activism in conformist Japan, though here, too, dissent is civilised, pragmatic and carefully considered. Geographer and activist Hongei (28) can usually be found at the headquarters. ‘We are part of a long tradition,’ he says with some pride. ‘At Kyoto especially there were strong anti-war factions in the 1930s, and in 1925 several students here were arrested as Communists.’

They probably won’t be planning any occupations; and if there is any graffiti painted it is done on the walls of this basement or the odd demonstration banner, a few of which stand in the corner of the room. But the students are certainly not sitting on their hands, either. ‘The next big meeting scheduled here will make policies to support residents who can’t or won’t carry student ID,’ says Yosuke. But some bigger plans — like a rally against the Fukushima nuclear plant — are also cautiously being made for the coming year.

As they shut the metal doors again on their way out, Yosuke and Hongei pass a large graffitied vignette on the basement wall. ‘You have a hard time,’ the scrawling black letters read, ‘but must stick it out.’